An Interview with Alicia Tolbert, Continued

Alicia Tolbert

Alicia Tolbert is a dharma teacher and racial justice activist living and practicing in Los Angeles, CA. In 2010, she completed the Asian Classics Institute's four-year Buddhist curriculum alongside her mother, Marie. She has been studying and teaching Buddhist philosophy since 2005, with an emphasis on logic, refuge, and the bodhisattva path. Alicia took her lifetime lay and bodhisattva vows from His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Lotte Lieb Dula, of R4S, and Alicia Tolbert met during a pilgrimage to Manzanar, a WWII-era Japanese-American concentration camp, sponsored by National Nikkei Reparations Coalition and Nikkei Progressives/NCRR.

Lotte:

Welcome, Alicia; it's great to have you. Today, I’d love to discuss with you the nature of repair at the intersection of faith and our shared history. To start, though, you have some amazing stories to tell about your ancestry. Do you mind sharing a bit about your ancestors and what you learned while researching their history?

Alicia:

Sure, my pleasure. So, I’ll start with my 2nd great-grandfather. For simplicity, let's call him Grandfather Andy.

Lotte:

How did you learn about this ancestor?

Alicia:

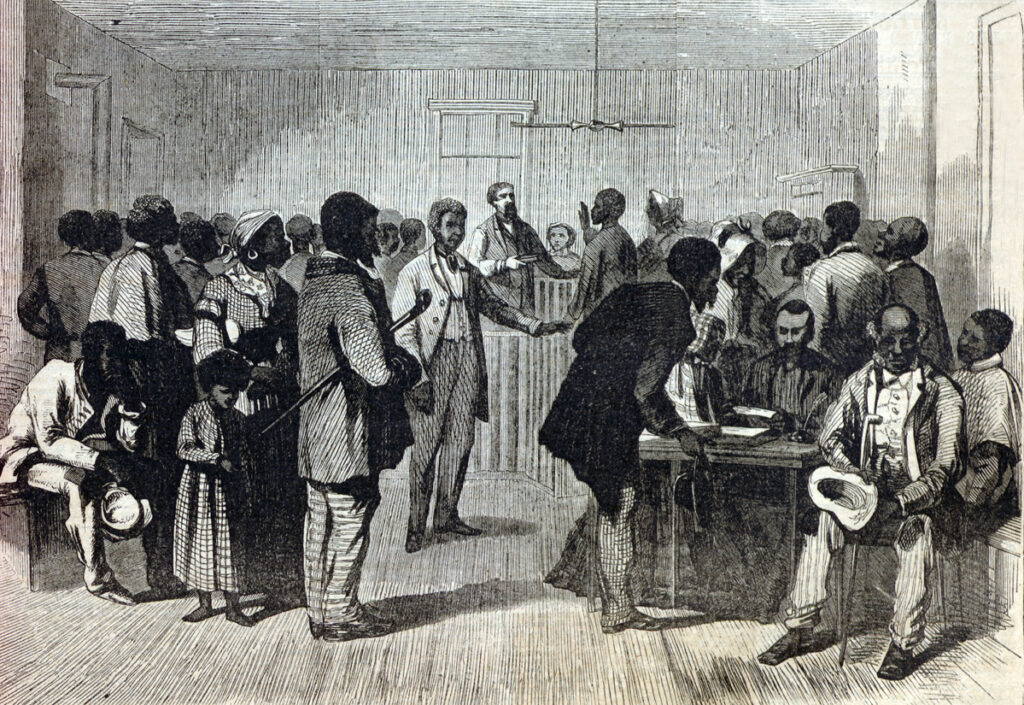

Believe it or not, I found his last will and testament online. His name was Andy Wilfong, and he had been enslaved in North Carolina. As a young man, he was sold away from his mother to the son of his original owner. They moved to South Carolina, where he was eventually sold away from his wife and child. He was sold to someone who allowed him on holidays to visit his first wife and child until he was freed.

I’ve kept googling through the years and found that he and 12 other formerly enslaved people founded the Black community where my grandmother and mother were born. It’s called Mount Olive, Arkansas.

They pooled their land and their resources, and this community still stands to this day. So, they were shielded from a lot of the horrors that formerly enslaved people had gone through and were able to build a little bit of wealth in terms of land ownership. For instance, Grandfather Andy had timber on his land. So, that has been a continual source of economic enrichment for generations of our family. I also have some cousins of my mother's generation who knew him. My mother knew him as well. So, I was able to glean a few stories about his leadership in the community and what a great man he had been. His nickname was Big Shot, so that tells you a little something about him.

"They pooled their land and their resources,

and this community still stands to this day."

Lotte:

That’s wild! Do you remember any other stories about him in particular?

Alicia:

Yes – one sad story and one that shows the beauty of his generosity.

So, Grandfather Andy had a creosote soak, which was, at the time, what a lot of farmers used to keep ticks and other pests off their livestock. He allowed all the other community members to bring their cattle to his creosote soak, to dip their cattle. And that was a service that he gave to the community.

He also donated, I believe it was $5,000, towards the establishment of the Mount Olive First AME church. He really was all about community.

Mt. Olive First AME Church

He also got into some trouble. He was a very proud man, and on one occasion, he was in the white part of town. A white farmer was telling a story, and as part of the story, he was mimicking a kick. Grandfather Andy thought that the man was going to kick him. So, he grabbed the man's foot, and the man was hopping around and got very embarrassed.

Grandfather Andy didn't leave it at that. He drove his horse and buggy 20 miles back home, grabbed his shotgun, and then came back and threatened the white gentleman. The way that he was saved was by other people in the community who apologized to the white man and told him that my grandfather was crazy. Andy had to get out of town for several months while things died down. So yeah, that was an incident that could have gone much, much worse.

"I found many of these stories online through interviews documented as part of the Freedman’s Project. Grandfather Andy's story is on record. Because of the unique nature of the establishment of Mount Olive by 13 black families, our family history is well-documented."

Lotte:

Having family stories like this is a real blessing. Did you find these stories online?

Alicia:

I found many of these stories online through interviews documented as part of the Freedman’s Project. Grandfather Andy's story is on record. Because of the unique nature of the establishment of Mount Olive by 13 black families, our family history is well-documented.

Lotte:

Did you hear any of these stories growing up?

Alicia:

I had heard some of these stories as little crumbs growing up. For instance, my great-grandmother Susan told my aunt, who is now 91, that she remembered the Yankee soldiers marching through Louisiana announcing the end of the war, so I suspect that Susan had been enslaved, but we don't know more than that.

I knew, for instance, that Grandfather Andy had gifted each of his children when they married a certain amount of acreage, except for one daughter who married a man that he didn't approve of. For instance, my great-grandmother, Hattie Wilfong, received quite a bit of land. She had 13 children, 12 of whom survived to adulthood. Each of those children received a parcel of land, including my grandmother. That land passed to my mother, and much of that land is still in the family.

Lotte:

Has your family had heirs' property woes like many other Black families? Or land theft?

Alicia:

Yes. Grandfather Andy had some land stolen from him. He was not able to read and write. So somehow, a white man was able to come up with some type of deed and lied and said that my grandfather had signed this parcel of land over to him. And unfortunately, that really affected his mental health for the rest of his life. He would have episodes; he would have to go into the woods for several weeks at a time into a cabin just to be by himself. And then, with so many heirs, there were a few squabbles, like someone had more land on the road, and other people had land pushed further back. So, there was a little bit of finagling, but for the most part, almost all the land was in the hands of a cousin because nobody else wanted to deal with the maintenance and upkeep. I had thought while my grandmother was alive that we might turn it into a spa. But that was going to be too much work around swamp conditions. So, we let that go.

Lotte:

Do you feel from your research that your Grandfather Andy may have received some form of reparations? How did he come up with the funds to acquire the land?

Alicia:

No formerly enslaved person received 40 acres and a mule. General William Tecumseh Sherman floated that idea, but it was shot down before it was enacted.

However, Grandfather Andy did, in fact, acquire 40 acres. It says in online documents that he purchased the land. So, I'm not sure if he was allowed to work and earn his own money and, therefore, be able to purchase land. But this land did come from his former owner. He took that land and found 12 others who had similar acreage or money, and they were able to form this wonderful community, Mt. Olive. Once he had the first 40 acres, he just kept buying land. And I am super happy to be one of his descendants! <laughs>

Lotte:

How would you describe the qualities that you've inherited from these ancestors? How do these qualities influence your views today about the work of repair?

Alicia:

Well, my maternal grandparents had to farm. So, they would go to school for most of the year, but when it was time to do the harvesting, they had to leave school. So, they felt that their education didn't go as far as they would've liked. They were quite firm with my mother that education was going to be her key to success. So, my mother was a first-generation college graduate, and many, many of my cousins in my mom's generation went to college and pursued advanced degrees, as did my mother. So, I'm quite thankful that my grandparents were adamant about that.

On my father's side, my father's brother created a gigantic family tree, and we did not come across any enslaved people.

My father's family is from New Orleans, and he was able to trace back to 1715. So, it looks like my father's side of the family may not have been touched by slavery somehow.

I think that the pride of having an education, having come from people who work very, very hard, is something that has been with me my whole life. So, I had two things going for me. We were surrounded by educated people, by people for whom that was a big deal. Then, the idea that our ancestors had gone through so much to ensure that we didn't have to. So, it was never a thought in my mind that I wouldn't work hard knowing that people had literally put their lives on the line so that I could be here.