REPOSSESSIONS: An Interview with Bridget R. Cooks, PhD

Bridget R. Cooks, PhD is a scholar and professor of African American studies and art history at the University of California Irvine. She is also an independent curator and the curator of Repossessions, an art exhibition that just debuted in Los Angeles at the California African American Museum.

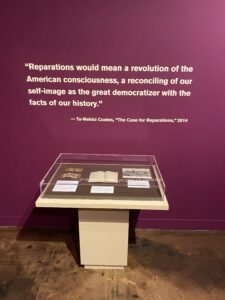

Repossessions is a group exhibition inspired by the concept of reparations: the effort to repair the economic and psychological devastation caused by slavery for descendants of enslaved African Americans. It presents the work of five Black artists commissioned to create artworks based on documents from the enslavement and Jim Crow eras in the United States. Chelle Barbour, Marcus Brown, Rodney Ewing, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle (Olomidara Yaya), and Curtis Patterson each offer insightful ways to understand the significance of the original documents, which were offered to the artists by white families working toward repair through

an initiative of The Reparations Project in collaboration with Reparations4Slavery that date from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Using a variety of visual strategies, the newly produced artworks contribute to viewers’ understanding of the long aftermath of enslavement and the need for reparations.

"The idea of Repossessions is to give objects of ephemera from the enslavement or Jim Crow eras to Black artists to transform. For instance, we currently have a plantation map, a plantation ledger, a sharecropping photograph, and Confederate money, just to start with this first group of five artists."

R4S:

Bridget, so glad you can join us! Please elaborate on the concept of Repossessions. As you envision it, what do you hope to accomplish with Repossessions?

Bridget:

Sure, thanks for having me! The concept was Sarah Eisner's idea; she brought me in to help develop the concept and curate the pieces she and Lotte Lieb Dula hoped to commission.

The idea is to give objects of ephemera from the enslavement or Jim Crow eras to Black artists to transform. For instance, we currently have a plantation map, a plantation ledger, a sharecropping photograph, and Confederate money, just to start with this first group of five artists.

The artists featured in this first exhibition are Chelle Barbour, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle/Olomidara Yaya, Rodney Ewing, Curtis Patterson, and Marcus Brown. Joining us in the next iteration of the exhibition will be Veronica Jackson and Lava Thomas. Each of these artists has received an object from the historical eras and has been asked to create an original artwork inspired by them.

"The show really models a way in which communication can happen between descendants of enslavers and descendants of the enslaved. It gives them an opportunity to address their respective histories and, hopefully, imagine alternative futures through these creative expressions."

R4S:

R4S:

What do you find most powerful about this first iteration of the show? How did the artists respond to the invitation?

Bridget:

The show really models a way in which communication can happen between descendants of enslavers and descendants of the enslaved. It gives them an opportunity to address their respective histories and, hopefully, imagine alternative futures through these creative expressions.

As a jumping-off point, two things were consistent when I talked to the artists about the project. Number one – they couldn't believe that there were two white women who separately created two organizations to support African American reparations. It felt like a kind of science fiction premise, but they trusted me and then felt excited to have access to these materials.

Number two, all of them had at one point thought about a project they would do if they had access to those materials, but there's no polite or realistic way to have that kind of access. And so, by working with Lotte and Sarah and their organizations, Reparations4Slavery and The Reparations Project, the artists can engage in a kind of conversation that would typically not be possible. So, the project, as an exhibition, opens a channel for communication between donors and artists and engages viewers to consider the case for reparations, how they are implicated, and how they might get involved.

"...there are the works by Curtis Patterson and Marcus Brown. Both artists work with the two pages from the Paxton historical ledger."

R4S:

As a follow-up question, how did your concept for the exhibition evolve as you began working with the artists? Did your conception change over time?

Bridget:

Well, as a curator, it's important for me to let the artists lead the way. They have these alternative worlds in their heads. I love working with artists because I get to be welcomed into their world for a moment, and it's always inspiring. So, I wasn't sure exactly what the resulting art would be. And each of them had completely different ideas.

Uhuru Now (2024) by Curtis Patterson

Chattel (2023) by Marcus Brown

For instance, there are the works by Curtis Patterson and Marcus Brown. Both artists work with the two pages from the Paxton historical ledger, from Lotte’s personal archive, but the approach is completely different. Marcus Brown’s piece is interactive. You have to touch it to activate the sound element. You're hearing an original composition, which gives the exhibition a kind of spiritual tone. You can hear it anywhere in the gallery.

Curtis Patterson, who usually works as a sculptor, created a two-dimensional piece; it has so many layers of symbolism and is really powerful.

"Another example is the work by Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle/Olomidaya Yara, where she has taken these very large prints of two Confederate dollar bills, a $2 bill, and a $5 bill from Sarah's family archive."

THEY: Harriet’s Reprisal [The Expulsion] (2024) and THEY: Harriet’s Reprisal [The Deluge] (2024) by Kenyatta A.C Hinkle

Also, many people know nothing about Confederate money; she's showing us other ways we could think about that symbolism. She was particularly inspired by Harriet Tubman and the idea that she might appear on a $20 bill. So, thinking about currency, the value of Blackness, and nationhood, the symbolism has many layers.

"Repossessions creates a cultural connection as well. For instance, my family members were talking to other people in the space; something in this show connects everyone. And that’s part of my role as curator, to help facilitate people’s curiosity to invite these conversations."

R4S:

You brought your family to tour the exhibition. What was it like for your family to tour the exhibition, to enter that space?

Bridget:

It was really a privilege to bring my family. My mother had never seen Confederate money before. “The nerve!” she said when she saw Hinkle/Yaya’s collages. She was shocked that Confederate currency even existed, so the exhibition provided a personal connection to this history. Repossessions creates a cultural connection as well. For instance, my family members were talking to other people in the space; something in this show connects everyone. And that’s part of my role as curator, to help facilitate people’s curiosity to invite these conversations.

It was really a privilege to bring my family. My mother had never seen Confederate money before. “The nerve!” she said when she saw Hinkle/Yaya’s collages. She was shocked that Confederate currency even existed, so the exhibition provided a personal connection to this history. Repossessions creates a cultural connection as well. For instance, my family members were talking to other people in the space; something in this show connects everyone. And that’s part of my role as curator, to help facilitate people’s curiosity to invite these conversations.

"...you think about something being repossessed, as in something you couldn't make payments on. And so, there's an implied reference to value and bankruptcy, of taking something back. The term bankruptcy also alludes to the repulsive system of slavery. "

R4S:

Let's move back in time, to the inception of the project. Sarah Eisner of The Reparations Project had commissioned the first piece of art, really the inspiration for the exhibition. How did you meet Sarah and become involved with this project?

Bridget:

Sarah and I met in 2020 in Palo Alto. We met at a closing event to celebrate The Black Index, an exhibition I had curated. Later, she mentioned that she had this family map of areas in Georgia and South Carolina that she had given to the artist Rodney Ewing. She sent me an image of the artwork Rodney had created from the map and asked what I thought about creating more works like that from ephemera. And we began to really think seriously about how this might be accomplished.

R4S:

How did you come up with the name Repossessions? What does that name mean to you?

Bridget:

Bridget:

First, I like the power of the word possession. It works in different ways: for instance, the idea of things you can own. Or the idea of being possessed by a spirit or a demon. And the related idea of someone having control over another body.

Then you think about something being repossessed, as in something you couldn't make payments on. And so, there's an implied reference to value and bankruptcy, of taking something back. The term bankruptcy also alludes to the repulsive system of slavery, that the idea of enslaving another person, to work them, to kill them, to damage the generations to come, is a morally bankrupt idea.

And a question comes to mind: who owns history? What documents are in Black archives vs. white archives? What happens when a group of people encounters something that is not in their family’s possession but is connected to them in some way?

The relationship between those ideas is really powerful and intriguing to me. So many layers and associations.

Repossessions is a way for Black artists to take objects out of white archives that relate to Black history and make commentary on them.

"My hope is that as the exhibition travels, there will be an object from a personal archive or maybe a state or institutional archive that will be selected for a local African American artist to respond to in a new artwork."

R4S:

How would you connect the concept of repossessions to reparations?

Bridget:

One powerful thing about the exhibition is it's not making a case for a particular law or form of reparations. Both organizations are looking at other specific ways in which the idea of repair can be enacted. For example, Sarah and Randy are funding legal work to try to make a difference for thousands of Black families living on land they don't have a legal deed to prove ownership. Lotte’s and Briayna’s project, Reparations4Slavery, is about education, particularly for white people.

One powerful thing about the exhibition is it's not making a case for a particular law or form of reparations. Both organizations are looking at other specific ways in which the idea of repair can be enacted. For example, Sarah and Randy are funding legal work to try to make a difference for thousands of Black families living on land they don't have a legal deed to prove ownership. Lotte’s and Briayna’s project, Reparations4Slavery, is about education, particularly for white people.

White people will listen to you in a way that they will never listen to me. So, there's something really savvy about how you both engage white people.

R4S:

What are your hopes for local partnership as the exhibition travels?

Bridget:

My hope is that as the exhibition travels, there will be an object from a personal archive or maybe a state or institutional archive that will be selected for a local African American artist to respond to in a new artwork. That way, every time the show travels, there will be a local element that addresses the history of enslavement or Jim Crow, and its legacy in that geographic area.

For instance, we hope the show will go to the Fredericksburg Area Museum in Fredericksburg, Virginia. This museum has inherited their local slave auction block, which had been on the corner in the neighborhood. The community there felt they needed to do something about this auction block, so it's been moved to the museum. Now, it's not ephemera in the way that we think about a photograph or a document, but it is a physical legacy of enslavement. So, adding a local component is another way to expand the show with regionally based artists and different objects as part of that collaborative process.

"One of the themes that has emerged is the idea of spirit, of respecting the ancestors. The artists see the exhibition as an opportunity to give voice to people whose names aren't necessarily recorded."

R4S:

What is your hope for how Black people will respond to the exhibition?

Bridget:

As with all my exhibitions, I seek Black validation. The space should feel safe. And I want people nodding their heads when they see the artwork. I’m hoping they'll be surprised by the whole project: Black people and white people talking to each other about something we're not supposed to discuss but think about all the time. I want Black people to feel validated and to think about what reparations might mean for them personally.

R4S:

Please describe your interpretive approach.

Bridget:

Bridget Cooks with Surreal Plantation (2023) by Chelle Barbour

I listen to the artists; the labels are really inspired by the artist's own statements, and I want to honor their perspectives. One of the themes that has emerged is the idea of spirit, of respecting the ancestors. The artists see the exhibition as an opportunity to give voice to people whose names aren't necessarily recorded. For some, the artworks feel very personal, while others may be thinking about a larger Black collective. So those are some things I hope Black viewers can relate to.

Now, for white people, it’s a different story. If they're honest about history, perhaps this is a palatable way to start a conversation. They may think about what's in their own family archives. So, as the show travels, I'm curious to see if we'll hear from white people saying, “I was really moved; I have all this stuff; what can I do with it?” It's not just an abstract idea. These are real people, real stories, real lives.

"My work is about making the art and ideas of artists of color visible, particularly the work of Black artists."

R4S:

Where does Repossessions fit into your body of curatorial work? How might your work on the project influence your future projects?

Bridget:

The exhibitions I’ve curated so far have been pretty diverse; I've done a 19th-century landscape exhibition, for instance, featuring Grafton Tyler Brown, a Black man who passed for white in California. I’ve done exhibitions featuring 20th-century abstract art. I'm working on a second exhibition of Yong Soon Min, a Korean American artist, a retrospective that will open in Seoul.

Bridget Cooks with THEY: Harriet’s Reprisal [The Expulsion] (2024) by Kenyatta A.C Hinkle

Sarah and Lotte would be talking to white donors, I would be talking to Black artists, then bringing everybody together. I would love this exhibition to go on for years and keep getting bigger and bigger. So, I think Repossessions might influence future projects by allowing a more experimental approach.

"Overwhelmingly, Black people I’ve spoken to find the whole project very bold and savvy. It's not a quiet exhibition."

R4S:

Have you found any of the artists resistant to the concept for the show?

Bridget:

No! In fact, a couple of the artists in the show asked to be invited. I haven't found any resistance from artists so far, but I have found resistance from venues. I can read between the lines that the objection may have been to the concept itself. Donors and board members of museums, particularly in the South, are very conservative politically.

R4S:

What feedback have you gotten from Black people about Repossessions?

Bridget:

Overwhelmingly, Black people I’ve spoken to find the whole project very bold and savvy. It's not a quiet exhibition; the premise goes against racial norms, in terms of communication. There is a level of vulnerability for everybody involved. Not only the two organizations, but also the people who are donating their ephemera to be transformed, and the artists themselves.

Overwhelmingly, Black people I’ve spoken to find the whole project very bold and savvy. It's not a quiet exhibition; the premise goes against racial norms, in terms of communication. There is a level of vulnerability for everybody involved. Not only the two organizations, but also the people who are donating their ephemera to be transformed, and the artists themselves.

We're so far apart on the way that we understand this history; that's another reason why the exhibition can be so powerful, because here you have white people who are saying, “Yes, we know. We wish it were different, but it's not. Here's what we want to do about it now.” There's validation in the experience of having a white person acknowledging enslavement, their family’s role, and the legacy they have benefitted from.

"We're so far apart on the way that we understand this history; that's another reason why the exhibition can be so powerful, because here you have white people who are saying, “Yes, we know. We wish it were different, but it's not. Here's what we want to do about it now.”