REPOSSESSIONS: An Interview with Sarah Eisner

Sarah Eisner and Randy Quarterman are the co-founders of The Reparations Project, a multifaceted redress initiative created by the Quarterman & Keller Fund that seeks to narrow the wealth gap and promote equity by centering descendants of those who were enslaved and supporting descendant families of enslavers to pursue ancestral healing through repairing generational harm.

Repossessions is a group exhibition inspired by the concept of reparations: the effort to repair the economic and psychological devastation caused by slavery for descendants of enslaved African Americans. It presents the work of five Black artists commissioned to create artworks based on documents from the enslavement and sharecropping eras in the United States. Chelle Barbour, Marcus Brown, Rodney Ewing, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle (Olomidara Yaya), and Curtis Patterson each offer insightful ways to understand the significance of the original documents, which were offered to the artists by white families working toward

repair through an initiative of The Reparations Project in collaboration with Reparations4Slavery and date from the 1860s to the early 1900s. Using a variety of visual strategies, the newly produced artworks contribute to viewers’ understanding of the long aftermath of enslavement and the need for reparations.

"The idea of Repossessions is to give objects of ephemera from the enslavement or Jim Crow eras to Black artists to transform. For instance, we currently have a plantation map, a plantation ledger, a sharecropping photograph, and Confederate money, just to start with this first group of five artists."

Bridget R. Cooks, PhD

Curator

Read Bridget's Interview

"Randy and I started by doing things that were heart-pieces for each of us."

R4S:

Welcome Sarah, thanks for speaking with us! Can you share how The Reparations Project decided to mount an art exhibition incorporating ephemera from the slavery and Jim Crow eras?

Sarah:

Sarah Eisner and Randy Quarterman

Thanks so much. Randy and I started by doing things that were heart-pieces for each of us. It started with land preservation for Randy’s family. And we broadened that to include land preservation for other multi-generational Black families in the South, so land preservation became one of the three prongs of our mission.

The second prong was education. That's based on another family story, which involves the last living descendant of my ancestor George Adam Keller, who enslaved Randy's ancestor s. She donated 2000 acres of farmland in rural Georgia to the Georgia Baptist Foundation for scholarships. The family always felt pretty good about that, and about the fact that George Keller made sure in his wills to leave land explicitly to women, his daughters, not to be managed by anyone they might marry. He also explicitly named both Zeike and his wife, Grace Quarterman, in the land he deeded to them.

But I discovered that the scholarships had been awarded through the Georgia Baptist Foundation to three predominantly white, very conservative Baptist colleges in Georgia, and the GBF would not disclose what race the scholarship recipients were. Almost certainly, they were all white.

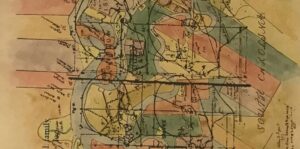

"...My mom kept showing me this map, a watercolor map. We didn't know exactly when it was painted, but she would remark on how beautiful it was. The watercolors are beautiful, but it's a map of rice plantations bordering the Savannah River. I felt conflicted..."

Strange and Bitter Fruit, inset, by Rodney Ewing

Now, my living family agreed funds should also be given toward scholarships for Black education. Georgia Baptist Foundation did not agree. Randy and I then decided we could do that on our own. And so that kicked off the education piece.

Our work around art started as an idea to amplify Black voices through writing. I had previously written a lot about privilege and my family history. However, I found keeping up with the blog format challenging, so we began considering other options for this third initiative.

At about the same time, my mom kept showing me this map, a watercolor map. We didn't know exactly when it was painted, but she would remark on how beautiful it was. The watercolors are beautiful, but it's a map of rice plantations bordering the Savannah River. I felt conflicted - I didn't really want to throw it away, but I didn't want it in my possession either, so what should I do with it?

"I offered him the map, saying he could do whatever he wanted with it. Rodney kept it for about a year, and then one day, he said he had made something."

Later, I ended up going to the Headlands Art Auction in Northern California. A piece by Rodney Ewing really struck me; it's a rendering of Trayvon Martin, a collaboration between Rodney and two other Black artists. Each artist has overlaid different pieces. For instance, the phrases, last words, and Black boy are layered into the work. That was the first piece of art I ever bought.

I ended up visiting Rodney at his studio. I thought later - he does so much of this overlay work, might Rodney want to work with this map? I offered him the map, saying he could do whatever he wanted with it. Rodney kept it for about a year, and then one day, he said he had made something. When I saw the finished piece, I was totally blown away. And that's when I started thinking about how different types of slavery-related ephemera could be transformed. The handing over of things related to the possession of other humans to descendants of those humans, who could go on to do whatever they wanted with the objects. It felt really important to give these things back in some way, which is why I think the title Repossessions Bridget came up with is brilliant.

"The main pushback I've gotten is from white people who say, “I would feel really badly if I had your history, but I don't.”

Bridget:

What have white people's responses to the idea of this project been?

Sarah:

I've been lucky in terms of my family’s response. Everyone from my mom to my 94-year-old aunt, who still lives in South Carolina, to my husband, children, friends and extended family, everybody in my family has been very supportive. In fact, no one has said, “Why would you do this, how could you do this?”

The main pushback I've gotten is from white people who say, “I would feel really badly if I had your history, but I don't.” The real challenge - and Lotte and I have talked about this many times - is getting white people in America to bridge that gap from thinking ‘only a few people have this history’ and therefore thinking, ‘I'm not complicit or culpable,’ and getting them to understand that they're a part of it too, even if they don’t realize it. The goal is an acknowledgment that this history applies to all of us, without white people recoiling in shame or guilt.

"...the hope is that through telling our stories, other people might get curious about their own stories – and about the history, wealth, and systems of the United States and how intertwined they all are with slavery and its legacy."

I do empathize with white people who have not yet discovered their connection to this history , simply as a white American. Their parents didn't tell them the history, or they haven't found a ledger. Ultimately, people are so self-interested, right? Until you find a very personal connection, it may not click for you. And so, the hope is that through telling our stories, other people might get curious about their own stories – and about the history, wealth, and systems of the United States and how intertwined they all are with slavery and its legacy.

"Initially, Kenyatta said she had to get used to just being in the same space with actual Confederate money. Once she was ready, though, she decided to go really big with the piece."

R4S:

Another artwork involved Confederate money from your family's collection of ephemera. What was the process by which these bills were transformed into artwork?

Sarah:

THEY: Harriet’s Reprisal [The Expulsion] (2024) by Kenyatta A.C Hinkle

As for these two bills, we don't know where they came from or why my ancestors saved them. For a long time, my mom thought we should give the bills to a museum. But after working with Rodney on the map, we thought offering them to a Black artist could be powerful.

Initially, Kenyatta said she had to get used to just being in the same space with actual Confederate money. Once she was ready, though, she decided to go really big with the piece. So, based on Lotte’s connections, we went to Magnolia Editions, and they made these huge, wall-sized prints of the bills.

"Both artists sliced these pieces of ephemera open and let out a deeper truth. They also somehow released a feeling I’ve had - that my ancestors are urging me to tell more of what really happened..."

R4S:

How has watching the transformation of your family ephemera into Black statements of liberation affected you? What’s in your heart?

Sarah:

You know, I can still pinpoint exactly what I felt when my mom showed me the map. But when I saw the version that had been transformed by Rodney, I just felt relief. That map is not just a map of plantation land anymore.

THEY: Harriet’s Reprisal [The Deluge] (2024) by Kenyatta A.C Hinkle

R4S:

Do you think the releasing of this truth reduces harm in some way?

"I hope, in some way, it shows the willingness of white people to admit what happened and to validate the pain."

R4S:

Do you think the releasing of this truth reduces harm in some way or creates a pathway for repair?

Sarah:

I don't know if that kind of harm can be repaired, but I know that the truth of the harm can be told. And in that way, a white family offering up photographs, documents, money, maps, whatever, to Black artists, it is in some way saying, “I'm sorry these things ever existed; now they're yours to do with as you will.” I don't know how much healing it does for the artists and the descendants of those harmed. But I hope, in some way, it shows the willingness of white people to admit what happened and to validate the pain.

"I also hope that visitors to Repossessions take away a sense of Black excellence and appreciate the incredible talent of these artists."

R4S:

What is the message you hope visitors to Repossessions take away with them?

Sarah:

I hope white visitors become curious about their own family history - what's in your closet? Literally and figuratively. I want people to go away wanting to know the truth. I define love as truth-telling and honesty; knowing our own truths and being open about this history allows us to love each other better.

I hope white visitors become curious about their own family history - what's in your closet? Literally and figuratively. I want people to go away wanting to know the truth. I define love as truth-telling and honesty; knowing our own truths and being open about this history allows us to love each other better.

I also hope that visitors to Repossessions take away a sense of Black excellence and appreciate the incredible talent of these artists. What would an entire museum look like if Black artists had more access to this kind of ephemera?

R4S:

Fantastic. What have I not asked you that you'd like to comment on to close out the interview?

Sarah:

I just want to say I feel so indebted to my mom, who provided the basis for this exhibition. The map and the money were things that her parents passed down to her. She grew up in a totally segregated South and I'm just so proud of how willing and excited she has been to contribute these things and to be part of this exhibition.

The same goes for you, Lotte; another thing I haven't talked about is how critical you have been to the show. I don't know if I would've brought up the idea to Bridget, if you hadn’t immediately said you wanted to participate and had ephemera to offer.

As Bridget often says, it's part of the power of the show that the two of us are working together to make it happen. I’m so proud of how everything has come together. And I'm just super grateful.