Interview with Maria Sharp Montgomery & Allison Thomas

Maria and Allison are linked by enslavement. Allison's ancestors enslaved Maria's on Gwynn's Island, in eastern Virginia's Mathews County. Together, they have researched the history of the Black families who were enslaved on Gwynn's Island and those who returned in 1870. In this interview, they explore their relationship and how working together to restore the history of Gwynn’s Island’s Black families constitutes part of the repair needed to heal the wounds of enslavement.

My ancestors didn’t just live here, they participated in creating the community. - Maria Sharp Montgomery

R4S: Maria, how would you describe your family’s history on Gwynn’s Island?

Maria: There were several generations of my family, descendants of Captain Smith, living on Gwynn’s Island. They had become the largest Black landowners there. They established a community, they bought fishing boats, they hired people. They were voting, and it was a big deal for a Black person to vote; there were poll taxes back then. My ancestors didn’t just live here, they participated in creating the community. And there were another 23 families buying land and establishing themselves.

R4S: Why was there no record of your ancestors’ lives on the island?

Maria: Our story had been erased and rewritten by the white community. When you run into people on the Island today, they say, “Oh, no, Black men never owned land here. That's just not possible.” But we found notarized deeds showing that Black families both bought and sold land there.

R4S: Maria, how did you originally become interested in researching your family’s history on Gwynn’s Island?

Maria: I had been told by my aunt and my mother that the family left Gwynn's Island because my great-grandfather, James Smith, had gotten into trouble. Considering history, sometimes that means they spoke up to a white person or had dealings with a white woman. That was what I was expecting to find.

R4S: What did you discover as you did your research?

Maria: We found that the true story wasn't as we had been told, or even as it was presented in the court transcripts.

The “official” story, obviously written by white people, was that the Black people just left one by one, to get better jobs between 1916 and 1920. But even the newspaper directly contradicts this version of the story. And there was this historic fight. They labeled James Smith an intoxicated troublemaker who got into a fight with white men. I mean, this is just how racism gets baked into how the story is told; this version remains in print to this day.

We found the court records: James Smith was found guilty of two counts of felony assault. He had a lawyer and an all-white jury, but only received fines of $35 and 30 days in jail, which is not bad, considering. The Smiths paid their fines.

Then we found other court records in the dead-papers file. Apparently, the judge believed that James Smith acted only in self-defense, and therefore should have been found innocent. And we think that that's why the judge gave him such a light sentence.

Unfortunately, this light sentence led to threats of more violence. This threat then caused everyone to leave the island.

R4S: What ultimately happened on the island?

Maria: Well, here’s the upshot: in 1924, Gwynn’s Island was dubbed, “the white man's paradise” in the Richmond Times Dispatch. In fact, it is still all-white today. The title of this article (White Man’s Paradise Nestles in Virginia Bay) is coded language implying that this is a great place to vacation because you won't have to worry about a bunch of Black people being there…

One of my cousins said, “I can only imagine the shape my life would have taken if I had known this history years ago. I thought that all I inherited from my ancestors was anger. Now I know they tried their best.” - Maria Sharp Montgomery

R4S: Once you discovered that your ancestors and the other Black families had been chased off the island, and that this history had been erased by the white community there, how did you work to restore this history?

Maria: One of the things that was really important to me, after I found out the truth, was to find a way to exonerate James Smith. Ultimately, we don’t have the kind of evidence required by the State of Virginia for a pardon or exoneration, but we are now able to create a new oral history.

James Smith goes from being labeled the ancestor responsible for the Black families leaving, for the downfall of the community, to the ancestor who owned a business, had a large extended family, and helped his daughter in her new household to establish her life.

One of my cousins said, “I can only imagine the shape my life would have taken if I had known this history years ago. I thought that all I inherited from my ancestors was anger. Now I know they tried their best.”

R4S: Have you met extended family members as a result of the genealogical research you’ve done?

Maria: Yes, I’ve met several cousins online plus others who live in Norfolk, where I live, and who have ties to the church where I grew up. My sister is still a member there; she knows several of them, but never knew that we were related. We are stitching the family tree, bringing the extended family back together.

R4S: What are your hopes for the future?

We want to find out where my great grandparents, my great-great grandparents are buried. Right now, the current property owners have closed off the alley, even though it contains cemetery space; now it’s private living space, and they have very publicly posted no trespass signs. We want this to change.

In Virginia, by law, you have to have access to a private cemetery, but we have to find it first. So that's part of the challenge.

R4S: What else have you done to correct the record?

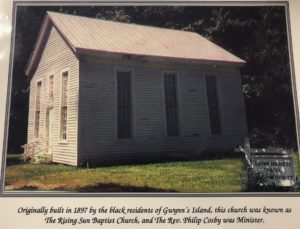

Maria: Allison and I, with the help of genealogist Sharon Morgan of Our Black Ancestry, put together a website, The Gwynn's Island Project, for the descendants of the Black families who lived on the island, to correct the record. The local newspaper covered this story, and the museum is posting that article in several places.

My own ancestors were so detached from the human suffering they caused. I ponder the documents I find deeply, trying to imagine the pain and suffering underneath them. Part of reparation for me is to feel the pain that my ancestors didn't feel. And to be willing to take that pain on - Allison Thomas

R4S: Allison, how has working with Maria contributed to the healing process for you?

Allison: Painful as it is, embracing and writing about my family history is a first step to racial healing. I have a favorite quote, by historian Julius Lester: “History is not just facts and events. History is also a pain in the heart, and we repeat history until we are able to make another’s pain in the heart our own.” My own ancestors were so detached from the human suffering they caused. I ponder the documents I find deeply, trying to imagine the pain and suffering underneath them. Part of reparation for me is to feel the pain that my ancestors didn't feel. And to be willing to take that pain on. And that it becomes a part of me so at least I can honor those enslaved people, the men, women, and children a little bit by taking on the pain that my ancestors could never grant them, with understanding and empathy.

R4S: How are you grappling with the issue of atonement for your ancestors’ actions?

Allison: I can't atone for my ancestors’ sins completely. The scale is enormous. My third-great-grandmother enslaved people that would be worth $69 million today, and that doesn’t count the land, and the advantages that have come down to me over the generations.

But I can work to change elements of structural racism in today's systems: work to end the school-to-prison pipeline, mass incarceration, advocate for fair housing, the list goes on and on. And I can work to support reparations at the national, state, and local level.

Personally, I try to tell the full truth of my family history, to uncover all those stories that were buried and erased. The rapes, the abuse, the trafficking in enslaved people back to colonial times, the whole thing.

My feeling was I need to be of service, I have something to offer. If I can find documents that help her connect with her ancestors, that's something I can do - Allison Thomas

R4S: Maria and Allison, let’s talk about how your relationship developed. Maria, when you contacted Allison, were you nervous about it? Have there been any bumps in the road? And do you have any advice for people going down the same path?

Maria: I had been contacting a number of people I'm genetically related to. Many times, they didn’t respond. But when Allison and I got together for breakfast, it felt like this is a person I already know, though we’ve only just met. And it's just been very easy, at least for me; we haven't hit any bumps in the road.

Allison: We had a shared task, we really wanted to get to the bottom of this mystery of what happened to the Black community on Gwynn’s Island. I didn't come to Maria crying, begging for forgiveness for what my ancestors did. My feeling was I need to be of service, I have something to offer. If I can find documents that help her connect with her ancestors, that's something I can do.

I want to go to Gwynn’s Island and stand there and think this is where my ancestors stood. - Maria Sharp Montgomery

R4S: What’s next for the two of you?

Allison: This journey isn't over. The Museum is already updating its history and posting our newspaper article. I am not sure it’s enough; it’s up to the descendants to determine that.

We plan to go back to the island. We want to walk those streets and look at those properties. I am now working with a state-funded group that is going to survey all the buildings on Gwynn’s Island. I have heard that the foundations of the Black school are still there. Plus, we want to find the two Black cemeteries.

Maria: I want to go to Gwynn’s Island and stand there and think this is where my ancestors stood. That my great-great-grandmother got up on a Saturday morning, and this was her view. And to think, these are the roads they walked along.

https://nonprofitquarterly.org/author/maria-sharp-montgomery-with-allison-thomas/