Interview with Danita Rountree Green

Danita Rountree Green, M.A., TLSC (R. Satiafa) is an author, playwright and trauma healing facilitator, conducting workshops addressing various forms of community trauma and race related issues in Richmond, VA.

R4S: Danita, could you briefly describe your family background? Have you been able to trace your roots to slavery?

DRG: Well, my grandmother was eighty percent Choctaw Indian out of Oklahoma – I’m the only child of my grandparent's youngest child. They had nine children altogether; I have an older cousin who remembers that when my grandmother and her siblings got together, they spoke a different language.

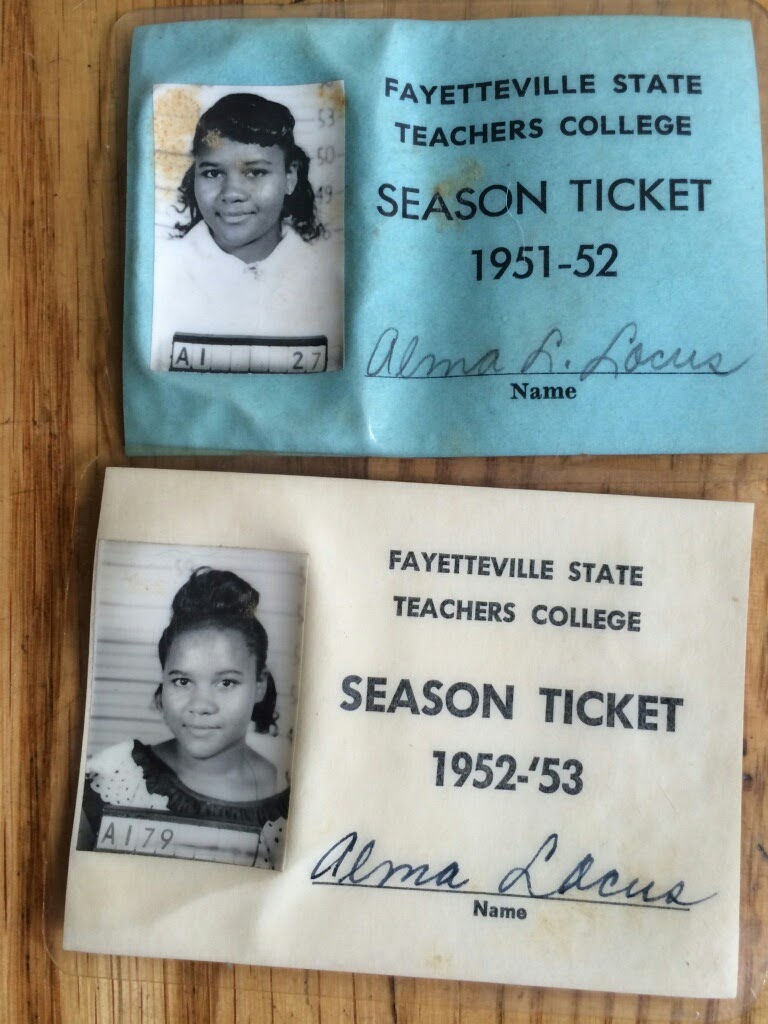

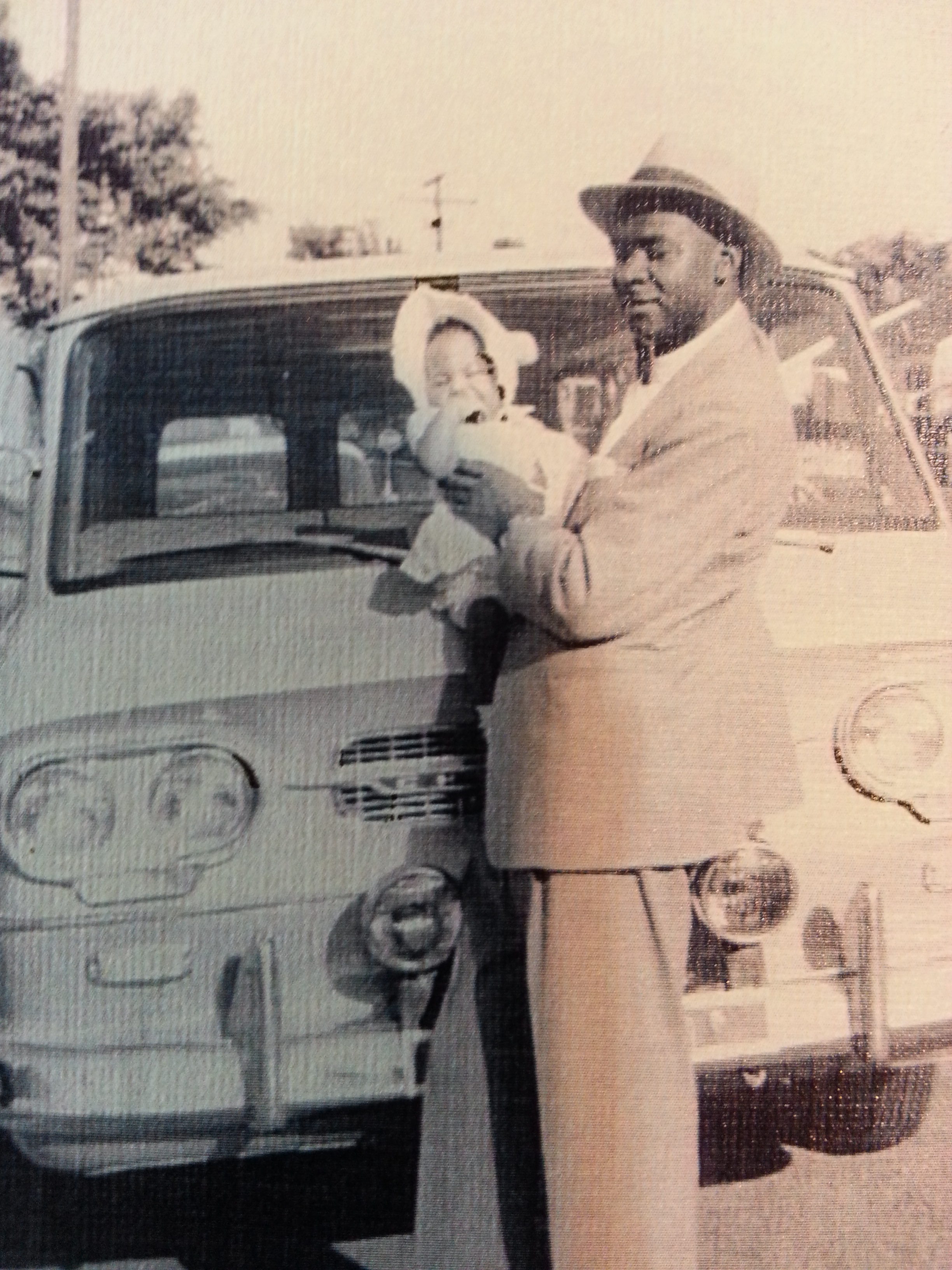

Now, as far as my connection to slavery, that would come through my great grandfather, Wiley Locus.

R4S: Were any stories about your ancestors passed down to you?

DRG: When I was coming up, our family stories were rather painful to hear; I really didn’t want to delve into that pain. For instance, my great grandfather had been a property-owning black man in North Carolina. He grew tobacco. Well, one season there was a wage dispute at market. His crops ended up being burned at harvest. There were some white land owners in that area that wanted his property. Let's just say they got it, if you understand my meaning.

There is another story that brings me a lot of pride and joy, though; it’s a story about a little wooden stool I remember seeing at my grandmother's house. Just the tiniest footstool, you can imagine – plain wood, only about a foot high. As a little girl, when we came to see my grandmother, she would put the stool outside on the porch near the front door, and we children would have to stand on the stool and say what we had learned during school that year before we could enter the house.

When my grandmother died, I inherited that stool. And so, when my kids were coming up, I continued the tradition – that makes five generations of children standing on that stool. It occurred to me that my great grandfather, who made that stool, wanted to teach his children to stand up and be proud, to raise themselves up. In fact, that generation of great grand parents did not go to school; the next generation was the first to go. So, not only was he teaching them pride and the physical symbol of raising themselves up, but each generation taught their parents what they were learning in school. How to read, how to write - what my grandparents called cipher. That's a very powerful legacy in my family.

My family raised themselves from being sharecroppers without an education to being educators themselves. And when I think of the history of that one small stool, what it has meant in the changing circumstances of our family, from people barely finishing middle school to getting that PhD: it all started with a man who built a little stool. In my heart of hearts, I would love to believe that my ancestors crossed an ocean to bring that tradition here to me.

R4S: Did your family experience institutional racism?

DRG: I am a child of the sixties, so, yes, I experienced segregation first, then integration. My mother was a freedom fighter in Virginia, a teacher in the Richmond public schools. She had to cross many lines to get better books, better supplies, better food, better everything in the education system. There were restrictions put on African American teachers; you couldn’t wear your hair certain ways, you had to look European. You know, I experienced some of that too when I came out of college.

R4S: Let's talk about reparations. You’re active in the reparations movement in Richmond. What are your views?

DRG: I believe we need to look at reparations exactly as the word implies: to repair something that is broken. And I believe that repairing starts on a very personal level and ends at the national policy level.

At the personal level, I think that we need to be very mindful of our thinking, on why we need to repair something we feel we did not break ourselves. For instance, when white people talk about slavery, I hear this all the time, “Well, I wasn’t there, that was something my ancestor did.” I feel this line of thinking is not germane; an entire people has been held back for 400 years.

At the national level, I feel strongly that the U. S. Government needs to step up and repair African Americans in all the areas we’ve been intentionally held back - through education, through economic means, and housing.

I look at this whole national narrative around reparations like this: we have a system in this country that’s broken, that doesn’t treat its citizens fairly. Now, I've never broken anything in my life that I didn't have to invest money in to repair, have you? This is not a repair that will simply benefit African Americans, it's going to benefit America itself. We’ve all made a joint investment in the United States; everyone should benefit equally from that investment, should be able to experience the full privilege of what it means to be a human being in this country.

R4S: What example do you have of reparations at the national level?

DRG: What’s happening at Georgetown University, with the students agreeing to raise their own tuition as a means of reparations for the history of enslavement there, that’s just incredible.

Here in Richmond, a bill, HJ 655, came through the Martin Luther King Jr. Commission of the Virginia General Assembly in commemoration and acknowledgement of African Americans who were lynched here in Virginia prior to 1950. We're putting up markers all over the state to acknowledge that this happened. It's part of the apology that the State of Virginia has given for this painful period in our country's history.

Another example: Farmville was a city in Prince Edward County that in 1959 decided it would rather close public schools than integrate them. Many of the white kids that had been going to public school in Prince Edward County got a government subsidy to go to private schools that were segregated. Many public schools were then closed, leaving African Americans without schools for six years.

Ken Woodley was editor of a newspaper in Farmville. He started his own campaign to help change government policy in that area to provide scholarships for African American children so they could go to good schools too. Two thousand scholarships were given out. That is an example of a truly reparational act taking place at the county and city level in Farmville. Yes. It can be done.

The name of Ken Woodley’s forthcoming book is “The Road to Healing, a Civil Rights Reparation Story in Prince Edward County”

R4S: What is your advice for white people just beginning to explore the idea of making reparations?

I think the hardest part for white people is dealing with the fear of change, the fear of ‘the other,’ of breaking rank from their family. It's hard to do this with our families, our friends, our religious leaders. If white people follow their own consciences, though, if they take a stand and do what they feel and know is right, they do the whole country a service. They will help turn the tide so we as a country can reach our full potential together, where all people in this country can thrive.