Interview with Felicia Furman

R4S: When did your family arrive in this country? What is your family’s background?

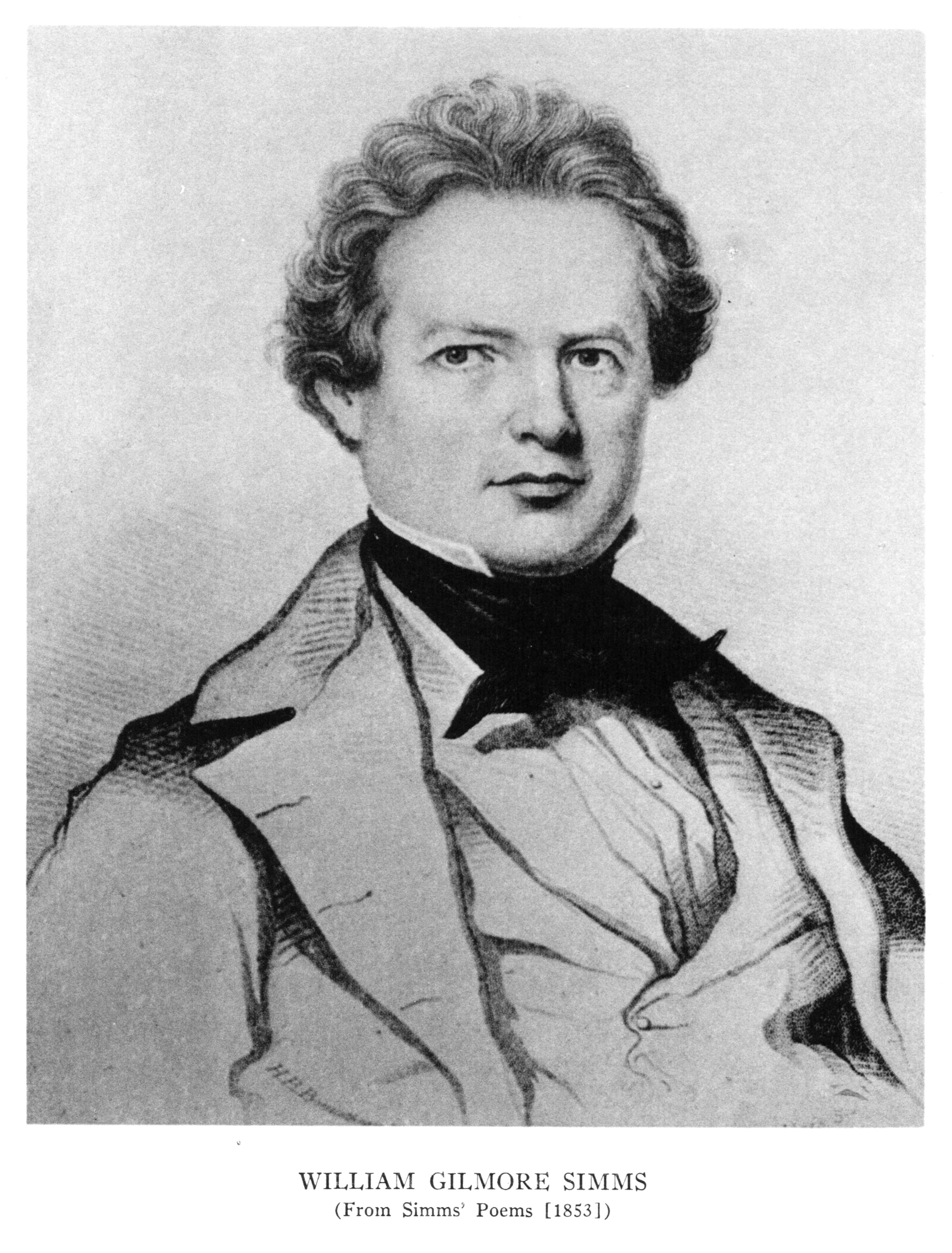

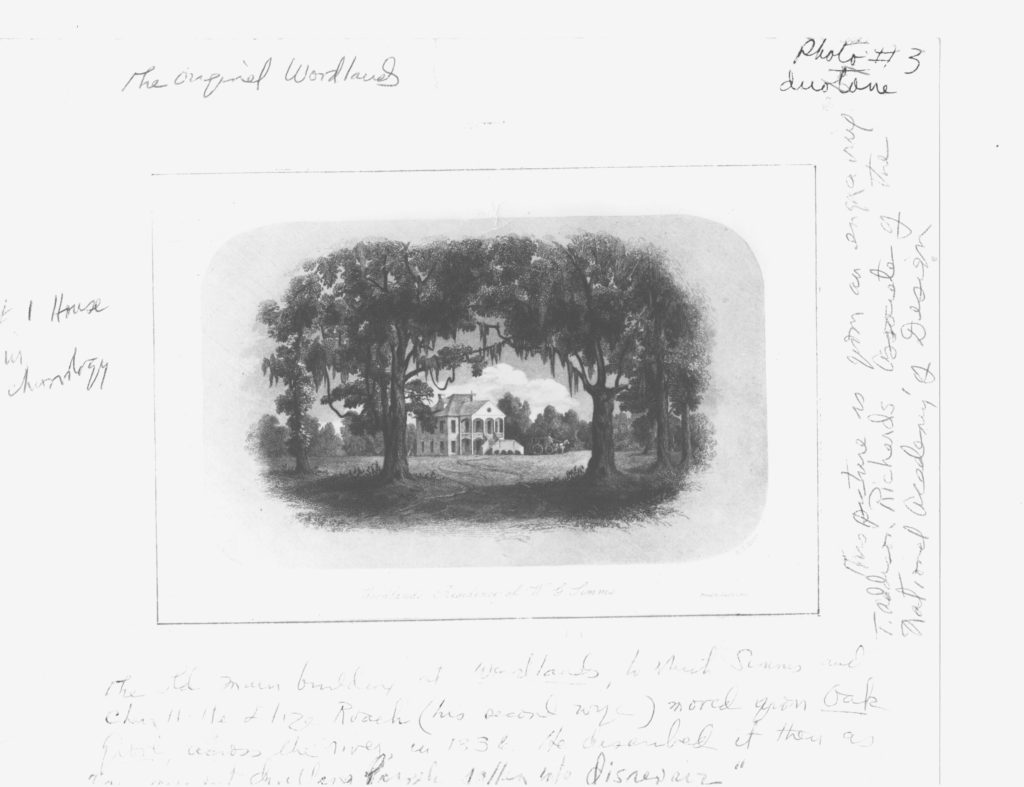

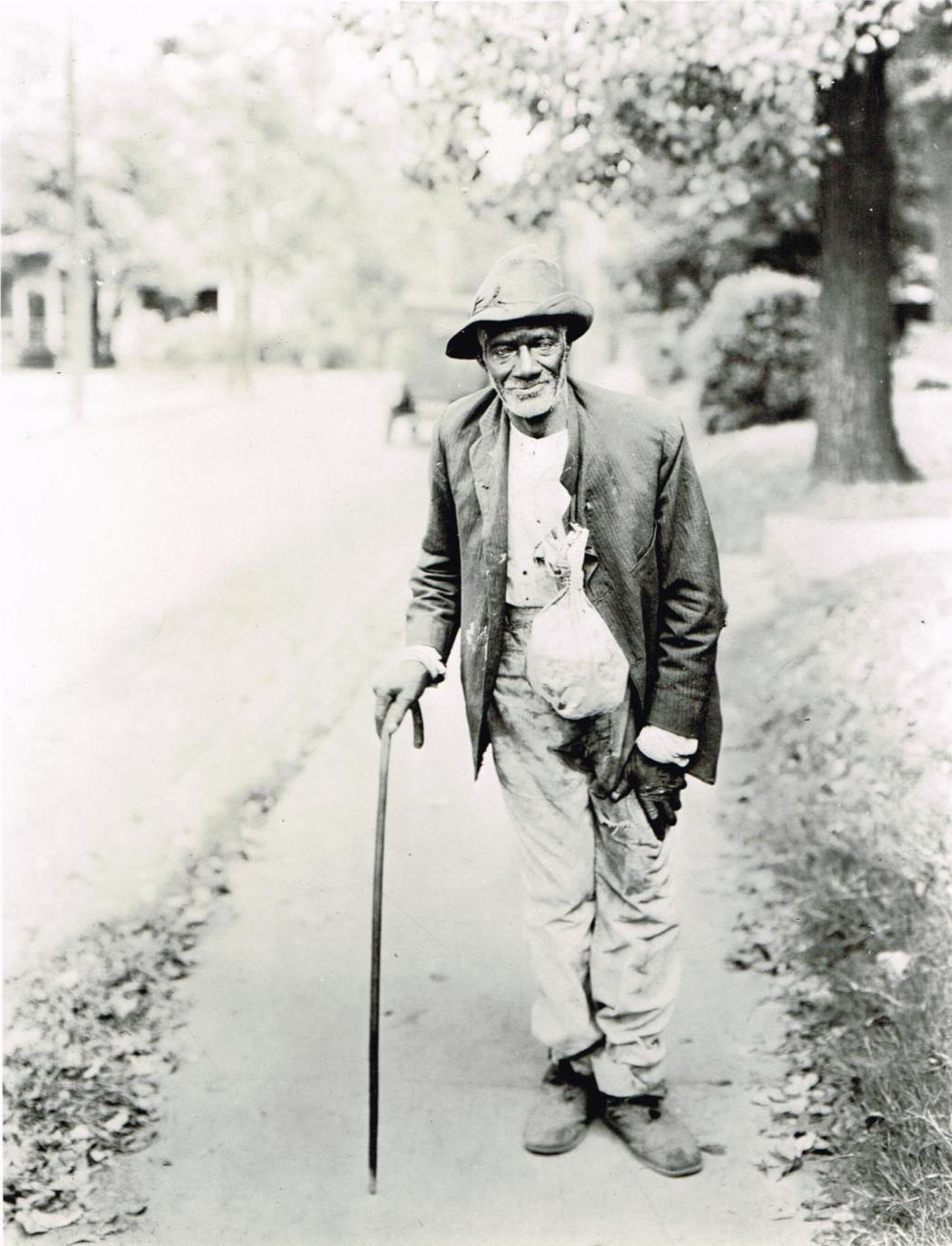

FF: My mother's family came to South Carolina as merchants and settled in Charleston in the 1700s. One of them, William Gilmore Simms, was a novelist. He married into a wealthy family in the upper part of the state and inherited, through marriage, a lot of land and slaves. He managed the family plantation, Woodlands. Our family is unusual, in that the land is still there and we’ve continued a relationship with the descendants of the enslaved. The families have stayed in touch, even up to the present day.

My ancestors on my father's side were also merchants. They arrived in New York state. At the time, land was being granted in South Carolina if you bought slaves and agreed to begin working the land. The idea was that settlers could earn revenue from farming and, in turn, this revenue would generate taxes. One of them, my ancestor James C. Furman, founded a small liberal arts college in South Carolina called Furman University.

So, both families arrived before the revolutionary war and both were merchants. Each saw slavery as a means to building wealth and forming a kind of aristocracy in South Carolina.

R4S: At what point did you decide to work toward racial justice?

FF: My family rarely spoke about our slavery past. It was common knowledge; we just didn’t speak about it. At some point I realized that even though my families had regular contact with African Americans, I didn't really know much about the African American experience. I happened to meet a professor at University of Colorado and ended up taking her class and learning a great deal about the realities of African Americans, especially in comparison to the realities of white Americans. I began to read books about slavery. Ultimately, I became horrified that slavery was such a big part of who we are as Americans, that enslaving people enriched so many families, including mine, and created the infrastructure of the United States.

R4S: You produced a film, Shared History, documenting your family’s history with slavery. What led you to make the film?

FF: My family’s 200+ year affiliation with these African American families is indeed unique, so, I decided to make the film to document it. The film required that I do a lot of historical and genealogical research, just to understand where the families came from. I wanted to correctly tell our stories.

R4S: Was there anything troubling about making the film?

As I began to record people’s family stories, I felt like I was taking something – taking their stories and making a product out of them. Something didn’t seem right about that. In retrospect, it followed a historical trajectory. My grandmother wrote history books, very racist history books, for the state of South Carolina. And, she had used the people at the plantation as characters in her book. I worried that I was repeating the same pattern by expecting people to share their stories with me. Though no one inquired about payment, I gave everybody I interviewed an honorarium as well as a location fee if we filmed on their property. So, at least there was some compensation. But, as I did the interviews, the historical harms became apparent. For instance, many of the descendants hadn't gone to high school, let alone college.

R4S: Did you decide to give reparations as a result of the filming?

FF: Yes – although I didn’t think of it that way at the time. I discovered that my ancestor had taught his coachman to read and write. That gave me an idea of how I could make reparations. So, I decided to take an inheritance I had just received and set up a family scholarship fund for the descendants of the enslaved people at Woodlands.

Over the years, I have received thank you letters from some of the children who have received the scholarship. Though I appreciated receiving the letters, it seemed backwards in a way It because, really the scholarship was my way of making reparations for my family’s enslavement of their ancestors. It was also an appreciation of their parents and grandparents’ generosity in helping me make the film Shared History. Ultimately, there is no act that can atone for what my family did to their families.

R4S: Have you been involved in reparations with Furman University?

FF: Yes. Furman has recently begun a reconciliation process, a coming together to figure out what to do about their connection to slavery. Buildings and scholarships are named after my slaveholding family.

Some horrific stories have come to light. James C. Furman was a Baptist minister and he was teaching a philosophy of religion class, something like that. He let his students out early so that they could attend a lynching in Greenville, South Carolina. After I heard that, I just felt like there was no redemption of this man. I also felt I could no longer just look at him as a distant relative.

Students have been very involved in the reconciliation process. Last fall we brought facilitators to the University to begin the conversation.

R4S: What advice do you have for people wanting to make reparations? If you were going to set up the scholarship fund today would you do anything differently?

FF: I would try to get other members of my family, my first cousins, to give money to the scholarship fund to really make it a scholarship from our entire family; that way, it would have much more meaning. Demonstrating to African American families that an entire family could get together to make reparations would be powerful.

R4S: How would you advise people who wish to make reparations but cannot locate the descendants of the people they enslaved?

I would make reparations to the community that sustained harm, to community medical facilities, local day care centers, after-school or church programs – organizations that benefit African American youth in that rural community. Supporting youth is critical.

R4S: What is your advice for somebody at the very beginning of the trail, just finding about their family history of enslavement?

FF: I would make sure you have your facts right. For instance, my family has handed down several stories over the centuries that I’ve found to be untrue.

One story that is still carried by my family today, even though they know it's not true, is that our ancestor gave 40 acres and a mule to the enslaved people who stayed on the plantation after the civil war. After much research we determined that they had not been given the land, the families had actually bought the land.

Another incorrect interpretation of a story was that an ancestor of the Rumpf family, Jim Rumph, who was enslaved at Woodlands, saved the plantation, saved our family, by working for a cobbler in town during the civil war and bringing back cash to help pay the mortgage. We always said, “He worked to save our family.” Well, one of his descendants said, “That wasn't to save your family, it was to save the plantation so that his family wouldn't be sold off.” I realized that my family had such “pie in the sky” notions, centering around our own importance, and little understanding of the true significance of our shared history.

Part of getting it right is to use your family records, whether they're in your own possession or in archives to get as much information as you can about who was on the plantation. It's important to find the names of the enslaved people so that descendants of the enslaved can find their ancestors.

Then look at reparations. I think you want to have as much information as possible about your family’s enslavement history so that your reparations plan is intentional and significant.

R4S: What would you like others to know about this process of reparations?

FF: Do Join Coming To The Table. I don’t believe anyone can do this alone. One of the benefits of being a member is listening to people's stories. Most white people have not heard African American people talk about the horrors of institutional racism in such an intimate way. You sit there listening to someone’s story that’s been handed down, just like yours has, but you realize that you could not have tolerated that level of pain, of persecution. You get upset; you start crying. Our inability to cope – it’s called white fragility. But somehow, you get through it. The strange part about healing is that, yes, African Americans want you to hear their story, but they also want to hear yours. Through it all you will get answers that will help you deal more effectively with racism the next time you run into it.

R4S: Any final thoughts?

FF: Making reparations is central to creating a society based on equality. Without reparations and an official apology, we will make no headway in achieving a world where a black child's dreams are just as achievable as a white child’s.