Interview with Fred Small

R4S: Fred, please describe your family’s heritage. Where did you grow up?

FS: My ancestors on my mother's side, whom I felt closer to, arrived here in the seventeenth century and settled in New England. On my paternal grandmother’s side, my ancestors arrived sometime during the eighteenth century and settled in the South. My paternal great-grandfather was a working-class Englishman.

I was born and raised in Plainfield, New Jersey. We grew up living, literally, at the bottom of the hill. The rich folks lived up the hill, and my family’s social circle gravitated in that direction. My parents belonged to the Plainfield Country Club, which I later discovered was segregated as well as restricted. Jews were excluded as well as people of color – unless you were serving staff in the dining hall. We lived near enough to the black and Jewish neighborhoods that my school, though overwhelmingly white, was not completely white and Christian.

R4S: What was your family’s socio-economic background?

I remember asking my mother when I was about twelve years old, “Gee, Mom, are we middle class or upper-middle class?” And she replied very forcefully, “We are upper class.” My mother was quite proud that she had an ancestor on the Mayflower. Social class was very important to her.

My father would never say how much money he made. We didn't talk about it. I would ask him, and the reason he gave for not telling me was that he didn't want me to blab to my friends. But I think it was more the reticence of the affluent—not because it's embarrassing, but because it's telling.

R4S: What did you learn about slavery in school?

FS: Growing up in the 1950s, I thought of myself as a Yankee, and therefore on the right side of history. Like many of my generation, I learned in school that the Union side was the morally right side in the Civil War, that Lincoln had freed the slaves, and that, for all I knew, slavery had never existed in the North. I thought that racism was this terrible Southern problem which, fortunately, the North had outgrown. Needless to say, I have learned a great deal since, but that’s what I learned in my youth.

R4S: When did you discover your family’s history of slavery?

FS: There is a story about a wedding gift in my family lore. I think I first heard it.

Julius Deming, an ancestor of mine who was a prominent merchant in Litchfield, CT, received two enslaved girls as a wedding gift from his father-in-law. This was at the turn of the eighteenth century. For years, I incorrectly assumed that the father-in-law was from the South, but in fact he was a Northerner. I found this surprising.

Julius Deming, an ancestor of mine who was a prominent merchant in Litchfield, CT, received two enslaved girls as a wedding gift from his father-in-law. This was at the turn of the eighteenth century. For years, I incorrectly assumed that the father-in-law was from the South, but in fact he was a Northerner. I found this surprising.

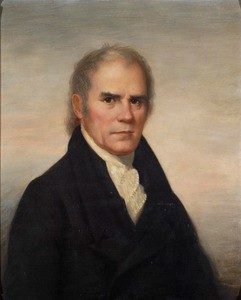

At some point I also investigated my Southern roots. I am descended from the brother of Senator Thomas Hart Benton. In the early nineteenth century, Senator Benton was one of most powerful men in the country. He is immortalized in John F. Kennedy's book, Profiles in Courage. Why? Because he lost his last election to Congress due to his opposition to the expansion of slavery in the United States. But what Kennedy doesn't mention is that Benton himself never emancipated the people he himself enslaved.

R4S: Do you know how many people your ancestors may have enslaved?

FS: We don’t know how many people my direct ancestor, Senator Benton’s brother Nathaniel, enslaved because his will was destroyed, apparently in a fire, but I expect it was a substantial number. Combining the Deming lineage on my mother's side, with the evidence I’ve found so far for the Benton lineage on my father’s side, I've identified 25 people enslaved by my ancestors.

R4S: When you first discovered your family’s history of slavery, what were your initial feelings?

FS: Well, initially the story of the wedding gifts seemed embarrassing and awkward, but as I looked more squarely at the reality of enslavement in my ancestry, a deep sense of shame developed. I know that it's not my fault. I wasn't there. But the fact that my ancestors include enslavers connects me personally to this abhorrent institution. I have benefited materially, culturally, and emotionally. I have benefited from the theft of the labor and liberty of human beings. And that's deeply painful.

R4S: Have you have you been able to trace privilege in your family, directly or indirectly, from that era? Is there any kind of family tradition that you can attribute to your family being financially better off because of enslavement?

FS: Yes. For instance, all the men in my family have gone to Yale. My mother would have gone, too, had she not been prohibited by gender from going—instead, she went to Mount Holyoke. My mother used to boast that the men in in her family went to Yale for every generation going back until they couldn't go to Yale because it hadn't been founded yet—and then they'd gone to Harvard! So you could say that my family bled Yale blue.

Yale itself has benefited substantially from income derived from slavery. They just changed the name of Calhoun College in the last couple of years. John Calhoun was, you know, one of the great apostles of slavery in American history.

R4S: How have your thoughts and feelings about your family’s history of enslavement morphed over time?

The feelings of shame are still there, at a gut level. However, I feel more than shame, I feel responsibility. I feel a special obligation to make amends to the extent that I can. And that feels good. That feels healing.

R4S: I'm wondering how your religious training has influenced your decision to make reparations.

FS: Well, I was raised Episcopalian. I grew up with the 1922 book of common prayer, where we recited, every Sunday, “Lord, I am not worthy. I am not worthy even so much as to gather up the crumbs from under thy table.” While there is a certain sense of guilt associated here, the upside of all that was the sense that doing the right thing was really, really important.

R4S: Did any events of your childhood influence your later interest in social justice?

FS: Absolutely. I was born in 1952. My first significant memory of the larger world, beyond my family, was the TV news footage from Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, when Bull Connor unleashed fire hoses and police dogs upon black children not much older than me. It broke my heart and made me feel that I had to do something about it, that the job of a human being is to prevent this kind of violence. That was an early event contributing to my social justice orientation.

R4S: Have you made any financial reparations to-date?

FS: My wife and I have given funds to help the son of a dear friend of my wife's go to college. My wife's friend is a highly educated African American woman, a successful professional who makes good money, but she is a single mom, and they have very little in savings or net worth. I believe the fact that they have significantly fewer financial resources than we do is absolutely a consequence of slavery and institutional racism.

We’ve never talked about this gift in the context of reparations, by the way; only in the context of need on their part and ability on our part. The primary motivation on our part is relationship, friendship.

R4S: What about reparations involving your time?

FS: I've been working with the Litchfield Historical Society, inviting them to document the history of enslavement, including that perpetrated by my ancestors, in the Litchfield Historical Museum. Also, to create a memorial for enslaved residents of Litchfield. I'm also hoping to help establish an internship at the Litchfield Historical Society to research the history of enslavement so that we can identify as many names as possible to memorialize on the grounds of the church.

I've also been working with the National Park Service at Longfellow House in Cambridge, MA. The house was originally known as the Vassall House; enslavement occurred in that house. I’m in discussion with Park Service staff to lift up that history in a more prominent way.

R4S: In what other ways are you making reparations?

FS: I left parish ministry in 2015 to work on climate issues and climate advocacy, which is my primary vocation. At this point, everything I do, I now do with an anti-racist lens. So, in my climate work, I am consistently discussing the links between climate justice and racial justice and environmental justice.

R4S: What advice do you have for someone who might be new to the path of making reparations or who's just discovered that their ancestors had some sort of slaveholding past?

FS: The point is to get beyond guilt, to act, to make amends. I think the most important thing that white people can do around race is to step out of the spotlight, to listen. At the same time, it's appropriate and helpful for us to acknowledge our own woundedness around race - which is very different from the woundedness people of color experience, but it's still real. Anything that disconnects us from our own humanity is a wound. And racism does that to white people as well as to people of color.

No one connected to their whole humanity would ever enslave another person. No one connected to their full humanity would ever abuse or oppress another person. We will never transform and surrender our racism without healing the woundedness that instilled that racism. I believe the first step to making amends is to begin down that path.