Interview with K. Melchor Quick Hall

K. Melchor Quick Hall is the author of Naming a Transnational Black Feminist Framework: Writing in Darkness. She leads a Quaker-based reparations workshop, Aiming for Justice: Race Reparations and Right Paths, which provides a brave space where US-based, white inheritors of wealth can enact partial and imperfect race-based redistributive justice

R4S: Melchor, please, describe your family background. What were some defining moments of your childhood?

KMQH: I was born in Washington DC, at a time when it was called Chocolate City, for its predominantly African American population. I thought everybody was Black for the first years of my life; I met and interacted with Black people from all over the map that was on my wall. And they all had complexions between my mother's light complexion and my father's dark complexion. Those years fostered a deep connection to diasporic Blackness that shaped our family life.

My first school was an intentionally all Black school called Roots, created by pan-Africanists and Black nationalists who were determined to raise whole Black children. I didn't know that white people existed as a group until I was maybe eight or nine.

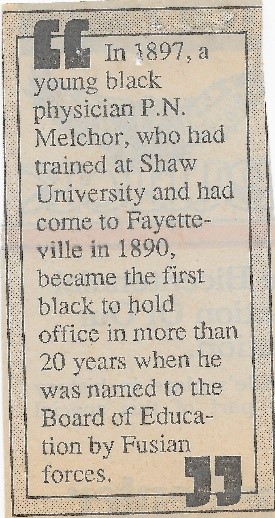

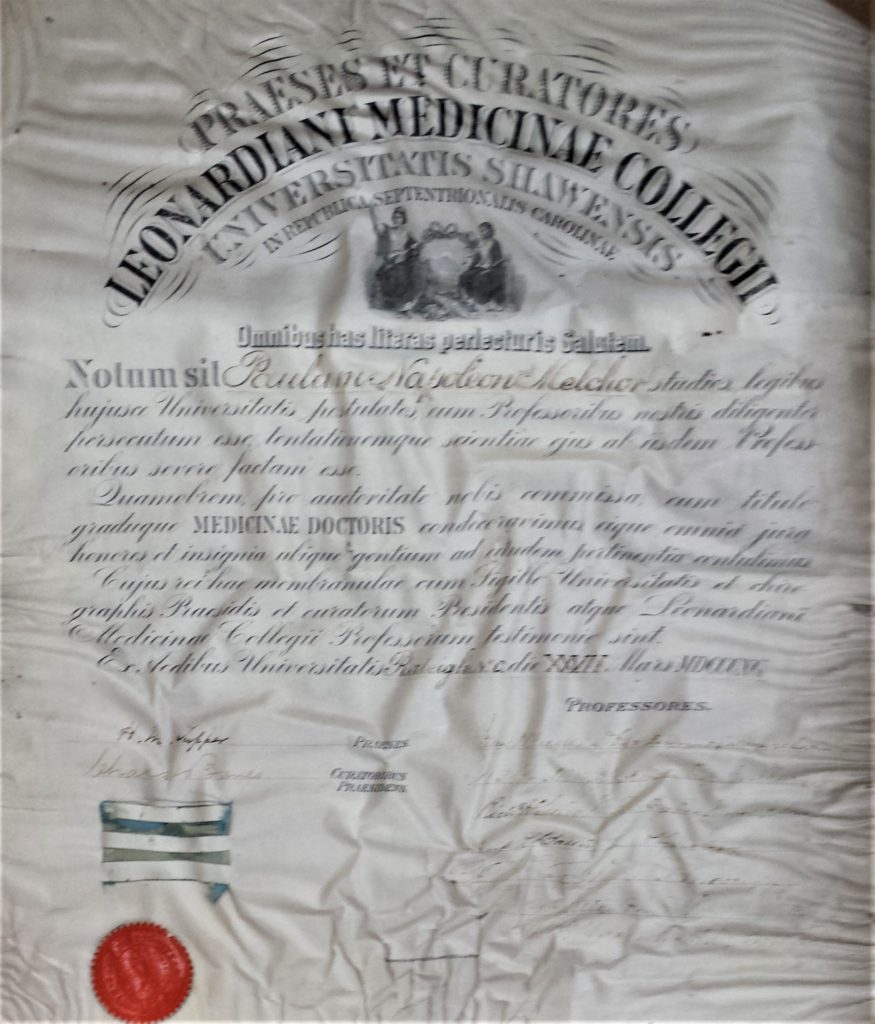

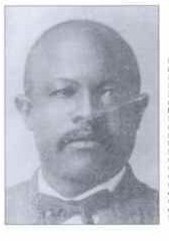

My parents divorced when I was young, so by third grade, my mother and I moved to Durham, North Carolina, while my father stayed in DC. Part of the reason we moved to Durham was because my mother had entered her doctoral program. She has a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; I happen to be a fifth-generation terminal degree graduate. So, my whole life, I’ve been surrounded by highly accomplished Black people.

What my parents had in common was an unapologetic, deep commitment to Black folks, Black education, Black liberation, Black health. My father was an ophthalmologist and he was always taking care of Black people's sight and vision; he did that on many different levels.

My mother studied political science and public policy and started a nonprofit. To this day, she works to ensure that African Americans have access to the many informal teachings that shape life’s opportunities in this country.

R4S: What was significant about the transition to Durham?

KMQH: I didn't realize that not all cities were chocolate cities, so it was a major cultural shock. The other kids didn't know the same nursery rhymes, the same stories I knew. Even the way I had learned the alphabet was different: I learned Ashanti to Zulu, C stands for Carver, etc., so I was really entering a different world. If you meet someone who looks like you, but tries to convince you that the two of you aren't fully human, how do you manage that? So, it was quite shocking to run into Black children who believed the mythology that is white supremacy.

Meanwhile, I immediately realized how inadequate some white teachers were for Black children; they couldn't imagine our intelligence, they didn't see the best in everybody in the community.

R4S: You’ve described the qualities of your parents and the communities in which you lived; how do these qualities show up in your reparations workshops?

KMQH: I consider myself really committed to Black life, the redistribution of stolen wealth and land, and its return to indigenous and Black communities. These values inform all that I do.

As for the workshops, I decided to format them as popular education style workshops, meaning that the goal is not for me to lecture some particular set of content, but instead focus on the experiences of the people who attend. With other formats, white people can be very much obsessed with performance, resulting in a discussion that is abstracted from the realm of people’s own power and privilege.

I begin by asking questions at the level of family, exploring the nature of family relations and the connection between kin networks, resource access, and personal choice. For instance, what about the father you're estranged from? You’re estranged because his politics were wrong, yet you have his house. I want people to tell that story out loud in order to release the truth and see how this has affected Black communities. This needs to be done in a group, to be witnessed. If you just take each person individually, you miss that collective understanding of white wealth structures.

Again, I think that keeping the word family in the frame of the discussion reminds white people of the humanity of Black folks, because otherwise it quickly devolves into a conversation about numbers. How much money do people have? How much do others want me to give? Do I have “enough” for my own family?

R4S: Is there a demographic you feel has the most trouble adapting to this approach to repair?

KMQH: Cis-gendered white men with a high degree of educational privilege tend to be challenged by this work. Part of the dynamic is related to how white men are comfortable engaging with Black women. For instance, there is often an expectation of friendliness. I’m not hostile, but I am clear, which often makes these men uncomfortable. Frankly, a relationship of exploitation and extraction needs to be intact for many of them to be willing to engage. Or, at the very least, they need to feel powerful—that they have been deferred to—or that they are participating in a game of attraction. And I don't do that.

There is also a desire for a calculating science. What is the value of my trauma? It quickly becomes a negotiation of the value of life itself. In one interaction, I believe that the white man with whom I was discussing reparations had settled on some amount of money that he thought my trauma, or my family, was worth! This, despite the fact that in three years of doing these workshops, not even one white person has been willing to tell me what they would charge me for one of their children.

Why do I continue? In part, because some of these people might someday embody the kind the values needed to lead this movement.

R4S: Reparations is about forming relationships. How do you approach that in the workshops? How does the Quaker environment support this process?

KMQH: I share as much as I ask other people to share. I think that sometimes people miss the delicate nature of decisions around how, and with whom, you do repair and healing. We have to have a commitment to one another. A certain compatibility of processes is necessary. It would be easy for people to sabotage the work by trying to heal with people who they wouldn't even play cards with.

One of the things I appreciate in working at Pendle Hill Quaker retreat center is the commitment to the process of listening, which is a slow and intentional, long-term commitment. In other environments, I see people really struggling to listen and to learn without performing what they think they know, and instead sitting with things for days, or sometimes for years. And so, that's part of the reason why I'm committed to doing this work in Quaker spaces, where listening is practiced as spiritual work. Listening is not a common practice among people with power.

What is required in this particular Quaker-inspired form of reparations work, which honors silence and listening and sees both as revolutionary and spiritual acts, is trust. And in this set of upcoming workshops, I'll be asking the group to trust me even more. Last year, people left with plans and letters to people and organizations to whom they intended to transfer resources. This time, they'll be asked to transfer resources right away, and they will have to trust that the money, which will not be controlled by white people, will provide whatever kind of support is desired by residents of Black neighborhood blocks affected by gentrification.

R4S: How do you guide participants beyond shame and guilt to that epiphany that can result in some sort of action?

KMQH: I don't deal in shame and guilt at all. Part of it is the way I go into the conversations. I say, “Tell me about the things that have allowed you to become the person you are today.”

Also, I'm not trying to punish people. That's really important because a lot of white people raised in this [white supremacist and punitive] society think that talking about what you've done or what needs to be fixed always leads to some form of punishment. It really takes some time for people to realize that I'm not trying to hurt them.

In the first year of the workshop, I gave an example because people were really struggling with the idea of stolen land and labor. I picked up someone's boot and brought it over to where I was. And I said, “What should be the process for you requesting the boot back?” The person got upset, and thought I was singling him out, making fun of him.

I stopped the workshop. And I said, “You don't know me very well, but I am not mean now, and I wasn't a mean kid, and I don't know what happened to you, but I am not trying to hurt you.” And, we worked through it. Once people can wrap their minds around the fact that I'm not looking for them to cry or to be hurt or to be damaged in any way, then we can talk about justice.

I'm not trying to do this in order to make some point to white people. There are a lot of people who are already making some important economic and historical arguments. I am trying to learn about what white mechanisms need to be undone in order for us to get to justice. I want to be clear that I wouldn't be inviting white people into this process, unless I believed that there was some information they had that I thought could be used to unleash justice. I am asking white people to show up, to do something that I believe that only they can do. And I can't lead it in the way that people often expect workshops to be led, because I don't actually have the answers. There are mechanisms and structures that I can't see. So, white people have to both show up and believe that I am not trying to hurt them, in order for us to identify those mechanisms and structures that must be dismantled in order for justice to prevail.

R4S: What is your advice for a white person just taking their first steps on the path of reparations?

KMQH: Normally, I would be asking them questions such as, “Well, what are you trying to do? What is it that you're uncomfortable with?” Often, there is discomfort that someone is trying to resolve around how they're feeling about their place in the world. My answer would also have to be dependent on what the person’s relationship is to Black people.

Listening is the beginning of the relationship for me. I want to know what this journey represents for people. I want to know why they're even asking the question. And then I respond to that because I honestly believe that this work is a way to save one’s soul, to honor one's humanity.

R4S: What have I forgotten to ask you?

KMQH: Or, perhaps I’ve forgotten to ask you something.

I think that this work of fully acknowledging the humanity of others is vitally important. We have to be prepared to listen and to learn from other people in a way that doesn't try to make them over in our own image or make their lives our agenda. I want people to stop and to reflect and to engage the people who are closest to them who they've, quite frankly, caused the most harm.

Justice has many paths; I want people to take all of them.