Interview with Kathryn White

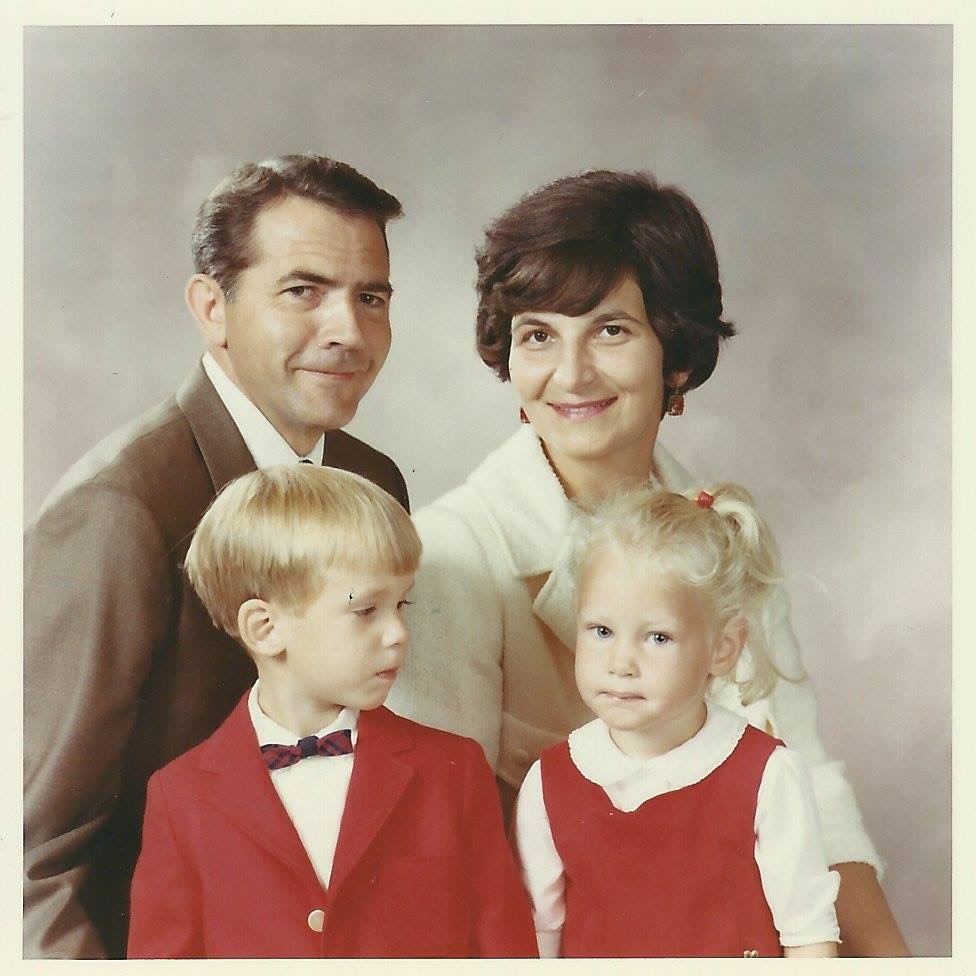

“When you’ve studied history—when you’ve begun to understand how racism has operated in this country over generations—it becomes imperative to stand your own family story up against the backdrop of what you’ve learned. My parents ascended into the middle class during a time when the G.I. Bill combined with redlining to create extraordinary economic opportunity for Americans of European descent. As I reckon with the history of systems that advantaged my family, while leaving others behind, I am morally compelled to invest in reparations and repair. To do this in community and through collaboration feels in itself to be an important step toward justice.” Kathryn White, co-founder of the Denver Foundation’s Fund for Reparations Affinity Group.

R4S: Kathryn, where did you grow up? How did racism show up in your community when you were a child?

Kathryn: Well, I was adopted by a family living in Topsfield, Massachusetts. We moved to La Habra, California, in 1969, when I was about a year and a half old and lived in a housing development that was mostly white. It was after the Fair Housing Act had theoretically eliminated redlining, but this neighborhood was predominantly white during most of my growing up years.

My parents were of the generation that didn't say racist things out loud. So, messages came across largely through body language and choices about friends.

One of my best friends growing up was a Latina neighbor whose family was one of only three Mexican American families on our block. They were treated differently. My mom and her bridge club friends seemed to steer clear of my friend’s parents.

The societal message seemed to be that Mexicans were bad, or inferior somehow, and certainly poor. It was hard reconciling these messages; my friend Jackie and her family were clearly not poor, but they were Mexicans. And my parents clearly looked down on them. There was nothing overt, but my mom had every opportunity to become friends with Jackie's mom. She never did.

R4S: Do any incidents of racism stand out?

So, my aunt and uncle lived in central Los Angeles, and two or three times a year, we would drive there to visit. I remember, we'd be getting off the highway, and my dad would say, “Lock your doors, kids.” So, I'd look up after my door was locked and I would see Black people. So, the message was that Black people are dangerous. My dad never said, “Look at those gang bangers over there.” But he never said, “lock your doors” any other time. You see what I’m saying. It took me decades to unlearn that behavior, decades, until I was well over 40 years old.

I remember the last time I did it because it was so poignant.

I was driving in my own neighborhood. I was at a stop sign, looked up, and I saw this Latino man crossing the street at an angle, heading behind my car. As I looked up at him, I locked my car doors. He heard the thud, looked up in surprise, and I could see this realization dawning, “This lady's afraid of me.” And it hurt him. I remember making eye contact with him and thinking, “Holy shit. I did that.” Later, I thought to myself, “Okay, I'm done. I'm not locking my car doors like this anymore.”

R4S: Have you been able to trace wealth accumulation in your family?

Kathryn: In my adoptive family, my grandparents immigrated from Germany, Poland, and Canada, mostly in the late 1800s. Their experience with wealth accumulation was probably connected to the definition of whiteness expanding in the late 1800s to allow for Italians, Germans, and Poles to become white. This new category of whiteness protected them from the discrimination many immigrants faced, for instance my Polish grandfather. He was a glassmaker; he changed his last name from Izbicky to Leslie to avoid ongoing discrimination in his trade.

As for my parents, the GI Bill is where I start to see concrete wealth accumulation. My father used his money from the GI bill to buy that house in Topsfield, MA, around 1949 or so. It was probably a neighborhood that redlining allowed my parents to buy into, then sell for quite a profit later when they moved to California.

If I had to pick out a couple of defining moments that led to my family’s accumulation of wealth in this country, one was my grandfather's ability to just walk into a courthouse and shed his Polish identity to become white. He had no idea that's what he was doing. He didn't know he was part of this larger historical expansion of whiteness. But he was able to change his name, and thus his standing, because he had white skin.

That, and the GI Bill allowing my family to ascend into the middle class from its working-class roots.

R4S: How did you come to the reparations movement?

Kathryn: Back in the early 1990s in Colorado, there was a backlash against LGBTQ rights. Now, this was on the heels of AIDS activism, and we were sick and tired of being fired from our jobs or beat up for being gay. People were dying, you know? Then Amendment 2 was passed in Colorado, making it illegal to create laws protecting LGBTQ rights.

I had noticed a real lack of allyship in the community. But then I thought to apply the standard of allyship to myself. Had I been a good ally for other groups of people? And the answer landed on me like a ton of bricks. Clearly, I had not been an ally to others, including people of color.

I was on an International Women's Week committee at the graduate school I went to, and I remember a couple of Latinas saying to me at one of the meetings, “You are just dripping with privilege and you have no idea.” And I remember saying, “Hey, we're all women here. We're all in the same boat, right? What do you mean dripping with privilege?” It was this classic, ‘take the plank out of your own eye before you comment on the toothpick in the other person's eye’ sort of moment; that’s where it started.

I began to study race and whiteness and then eventually when I inherited money from my aunt in 2015, I was just starting to understand the economic impacts of racism in this country. So, with some of the money I inherited, my partner and I started a small reparations fund at The Denver Foundation.

R4S: How did you decide where to grant the funds?

Kathryn: Well, we decided to focus on organizations founded and run by people of color that had a clear racial justice framework.

Harold Fields, who ran the Second Tuesday Race Forum, made a comment that really stuck with me: "You know, charity is about getting a tax deduction. And that means the schools aren't getting funded and the roads aren’t getting funded. So, why not just pay your taxes?” He planted that seed and I realized that reparations giving could be more direct, that you could skip the 501(c)(3) model altogether and find ways to give directly.

R4S: How did your thinking continue to evolve?

Kathryn: Well, there are some typical mental traps with the white supremacy mindset that I had to look at. Overthinking things, being focused on analyzing things and really wanting to have a lot of control is something I’ve done myself and seen others do. For instance, ‘only supporting sustainable organizations’ and focusing on what the metrics need to show. I had just recently learned the term white hoarding, right after I inherited, so I wanted to just identify some work in the community that needed funding, forego a big process, and just move the money.

R4S: Were there any pitfalls to doing that?

Kathryn: In the end it started to feel kind of performative because no relationships were developed in the process. At the same time, I didn’t want to be a burden, I didn’t want an organization to think they had to invite me out for coffee every year or create some new unique snowflake relationship-type for me. But to really effect change, to participate meaningfully, relationships are important.

R4S: What advice do you have for a white person who's starting out on the path of repair? What's important to know?

Kathryn: I think it's important for people to understand their family history in tandem with societal and world history. If you're reading a book about the great migration, where was your family during that time? Start having those conversations with cousins and parents and siblings – whoever knows your family history. Have those conversations with family members while they're still alive.

Then, it’s important to find ways to connect with people from all kinds of backgrounds in the racial justice movement. That way, when you’re ready to consider direct reparations, relationships of respect, of high regard with some context are already there. This forms the ground.

Lotte: Any final thoughts?

Kathryn: You know, five years ago, I would have said that House Bill 40 and a national reckoning was generations away. I would not have predicted we would be where we are now. I mean, we’ve gone from having 35 sponsors for HB-40 to more than 180 almost overnight. There's a very concrete opportunity in front of us. We shouldn’t waste it.