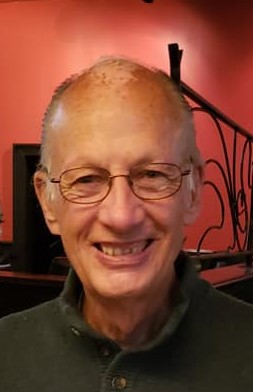

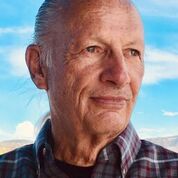

Interview with Rusty Vaughan

R4S: Rusty, please describe your heritage and how your family came to this country.

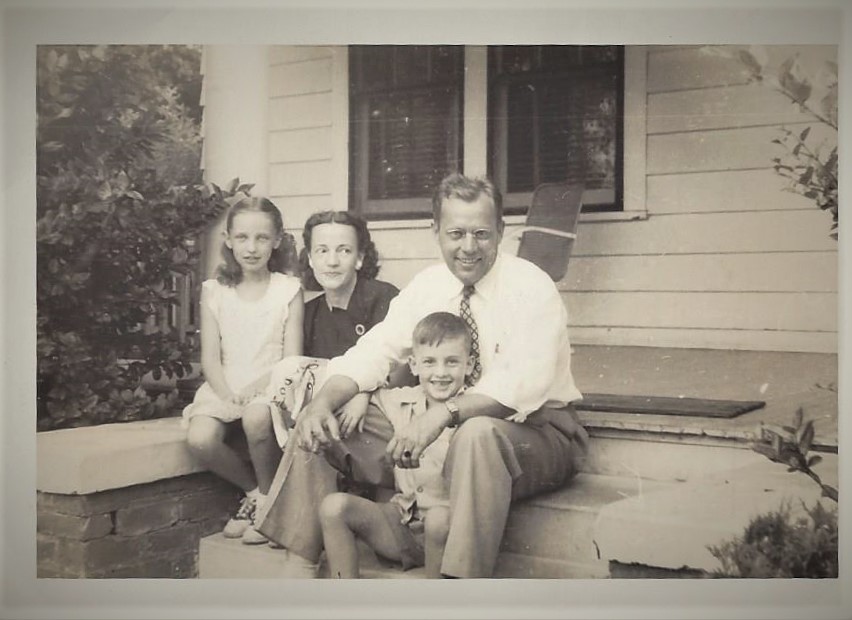

Well, I'm of Scots-Irish descent. The Vaughans came over in the late 1600s from southwest Wales and settled in various parts of Virginia. By 1792 the Vaughans moved to Grayson County, Virginia; all my Vaughan relatives remained there through many generations.

My father was the first to leave; he met my mom in Grayson county, then moved to North Carolina. I was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina in 1941. That's where most of my influences have come from.

R4S: Did your family have a slaveholding background?

RV: Not in my direct Vaughan line. However, some of my great grandparents’ siblings were slaveholders.

The way I found that out was through a Y-Chromosome DNA test. One of my DNA matches on FTDNA sent me an email and said, “Rusty you need to get in touch with Eric Anderson.” Well, I knew that name because he was a close DNA match to us, so I agreed to call him.

Eric Anderson happens to be African American. We had a long conversation, trying to find out how we were related. He told me his oldest known relative, a slave named Burl, was born in 1848 in Hopkinsville, Kentucky and that Burl’s father, according to family lore, had been born in Virginia. I asked Eric what he knew about Burl and he said, “I've walked on the farm where Burl and his mother were slaves. The present owner walked me by the area where the slaves were buried.” As it turned out, Burl and his mother were owned by the Samuel Johnson family and Burl was given to the son of Samuel Johnson upon his move to Missouri, around 1864-1865. He was there when he was freed and that's where he married and took the name Anderson.

I looked up the Samuel Johnson family; their farm, then in Hopkinsville, was adjacent to both an Anderson family - and a Vaughan family. Eric said he never heard the surname Vaughan until he got his DNA back and then found he is one and is related to me.

R4S: Could you talk about what life was like growing up; your attitudes about racism, your early views?

RV: Really, growing up I thought that the issue of race didn’t affect me. Those black people, they lived somewhere “over there,” the other side of the tracks, and we didn't mix. And, of course, I was never in school with a person of color or had a teacher of color; we were segregated. I grew up with colored and white restrooms, colored and white water fountains and colored and white theaters and restaurants - and, back then, I never gave any thought to it.

Let’s get back to Eric Anderson, my DNA match. Eric called me at one point and asked me if I would join him at national gathering being held in Richmond, Virginia. Not knowing what it was, but sensing it was meaningful to Eric, I agreed and that’s how I got involved with Coming To The Table. That was the CTTT National Gathering in 2012.

I went there on a Thursday, then found myself driving home on a Sunday, it went by that fast. There were so many revelations. I quickly concluded that my life had changed. I did not know what was going to happen next, but I knew that I could not unlearn what I had learned, and I needed to do something with that understanding.

Now, it took me a few years to define what had happened, but ultimately, I realized that was the first time I had been out of my “white bubble,” in a place where I was not in the majority. That's when the seed was planted: the understanding of my own racism and, the beginnings of my passion to dismantle racism, that’s where it all started.

R4S: How did your views begin to take shape?

RV: Well, after I attended Coming to the Table in Richmond, I began to realize that I might be part of the problem. What took me several years to understand is that I was the worst kind of racist there is. Previously, I thought racists where those guys wearing sheets and riding down the street at Ku Klux Klan parades and rallies. I thought those were the only white supremacists.

But to me the worst racist today is the one who denies being the least bit complicit. And, I’ve heard it said, “If you're white and you grew up in the United States, you're racist.” I've come to believe that absolutely.

R4S: Do you consider the racial justice work you are doing to be a form of reparation?

RV: Yes. For me, the process of changing has been gradual - no matter how much I work at it and no matter how much I read, I still have more work to do! I remember as a child, when my dad saw a mixed-race couple, he would come unglued and get really angry. Well, I was no different from him then; but when I came to understand those hidden biases, the micro-aggressions, let’s just say that I’ve had a lot of work to do. In order to dismantle racism in our community or our country, we have to look at ourselves first.

R4S: What were your early aha moments?

RV: I was in a group talking about racism at my church in Maryland, and people were telling their stories. One young couple that I considered to be white like me, told us their parents were from the Philippines and that they had experienced racism as recently as that morning. Sitting there listening to their stories, I thought to myself, “If this is happening to them, what must it be like for African Americans?” And, that's when I started reading and studying racism and trying to understand. So, my focus has been setting up Coming To The Table local groups – I’ve set up six so far - to bring white folks and especially white males into the conversation about race.

R4S: What advice do you have for somebody just starting out on the racial justice path?

RV: First - Forget about your granddad. And your daddy. It's what you did yesterday that matters. It’s your denial that is getting in the way of all of us coming together and understanding. I’ve seen nothing more effective than conversation and sharing stories and experiences. One can listen to 100 lectures but until he speaks about race and puts his feeling into words, there is little chance of anything changing.

Next – read about racism, repeatedly, with an open mind. Begin to understand - racism exists because of me. And it is being perpetuated because of my inaction. So, you want to read authors like Robin DiAngelo, Debbie Irving, Michele Alexander, John Hope Franklin, and others that understand this, then really look at yourself and your family history. Once you accomplish that, you have to start having conversations with other people. I personally believe that before white people engage with people of color, we need to talk amongst ourselves – try to get things straight, because otherwise we're going to embarrass ourselves and likely create a situation that will end the conversation before it evens starts.

Developing trust is important; you will inevitably say something offensive, but if the trust is there, you will be able to talk about it and not get upset with each other. My first experience with Coming to the Table was the first time in my life I had been trusted by people of color. That trust, that bond, enabled me to see a people and culture I had never met. Trust enables the beauty to enter and, I am sure, enabled me to give with grace for the first time…. at least a little.

An example of this happening at a conversation with two women of color: At their request, I had been giving my background and explaining how I came to understand racism, and I said, “I'm still making mistakes every day. I may have made one today, but I don't think I did.” Well, one of the women said, “Yes, you did.”

“Huh? What did I say?” I was genuinely surprised. She said, “Well, you told a story about this man that you met and tried to help. Rusty, you are talking down to us by saying you are trying to help us. I want you to know we don't need your help. We are your peers. We just want you to stand beside us – or get out of our way!” This is a perfect example – we white folks need to understand how we are complicit and how we perpetuate inequality with everything that we say and do.

That encounter was several years ago. It’s made a lasting, lasting impression. Oh, man, there’s hardly a week goes by I don't think about that encounter and learn from it.

Baltimore Sun: Hate Interrupted: Coming To The Table Offers a Way to Talk About Race

Capital Gazette: Faith Community Discusses Racism, Black Lives Matter.