Interview with Tamara Rhone

Tamara Rhone

Denver native Tamara Rhone devoted 45 years of her life to her passion, teaching African American history in the classroom, before retiring in 2021. Tamara co-led a 40-session reparations education series, which included study guides from the R4S portal. Tamara also serves on the board of the Denver Black Reparations Council.

R4S:

Tami, you taught social studies with an emphasis on African American Studies for 45 Years. After you retired, you co-led our 40-session Reparations course, “Uncovering History: Walking the Path of Repair.” What led you to the path of teaching?

TR:

Well, achieving a good education was always important for our family. As a child, I attended a predominantly white private girls' school, so my mother was always teaching me about Black history, since it was not taught at that time. Finally, in high school – this was the late sixties, and we were demanding change - our teacher agreed, became educated herself, and taught a Black literature class. So, I was exposed to James Baldwin and other Black authors -those readings really sparked the light for me. Then, when I went off to college, I took every ethnic studies course I possibly could as an elective because it fascinated me.

R4S:

How did you become interested in the reparations movement?

TR:

When I retired, I became very interested in finding solutions to all the societal problems I had been teaching about. How do we start fixing these things? And I felt a program of reparations was the best way to do that.

When I retired, I became very interested in finding solutions to all the societal problems I had been teaching about. How do we start fixing these things? And I felt a program of reparations was the best way to do that.

As an educator, I have the opportunity to educate people of all colors and all economic backgrounds about the movement for reparations. When you use that word, people tend to clutch their pearls – their checkbooks, debit cards, and so on. It’s important for people to know that there are many paths to repair and many things we can do to make this a better place. It’s not solely about financial restitution.

R4S:

How would you define reparations, then?

TR:

For me, reparations are about understanding that harm is being perpetrated: defining and acknowledging the harm, apologizing for it, and making sure that it doesn't happen again. Beyond defining harm, we need to fix it, and we want positive changes made that not only stop the harm but help everyone. In my view, when we all achieve, it's great for everybody.

Reparations are about understanding that harm is being perpetrated: defining and acknowledging the harm, apologizing for it, and making sure that it doesn't happen again. Beyond defining harm, we need to fix it.

R4S:

Why do you think calls for reparations are intensifying at this point in our history?

TR:

I think that we're at a point in this world where the negative impact of holding Black people down is really beginning to affect everyone. Look at West Africa. Africa is the wealthiest continent in the world. So why are Black Africans living in such poverty? We know about colonialism, we know about who's running the mines, we know who's stealing the land, who's cutting down the timber. Our environmental issues are coming to a head because of that kind of greed. The impact of that greed affects everyone. We're destroying the world – all to benefit a few at the top. Well, it’s impossible to harm others without harming yourself in the process. Reparations is about settling a debt for harms that have taken place over hundreds of years.

R4S:

Do we appear to be repeating history in some way? How would you compare today's environment with this country’s post-Reconstruction history? Is there a parallel?

TR:

Oh, for sure. We're in Jim Crow II. Our civil rights are being rolled back right and left. Consider what’s happening in Florida with public education.

We're in Jim Crow II. Our civil rights are being rolled back right and left.

Like I used to tell my students, they're not going to pass a law that says you cannot learn to read and write. They just won’t teach you. And that's what's happening right now in Florida. Education doesn't just end in the classroom at 3:30; it's got to be 24/7, especially when Black history is being erased. In Florida, the governor has stopped the public schools from teaching Black history, so the churches are picking it up. Well, we had Freedom Schools in the 1960s, so we're going to have to start Freedom Schools again. A full repeat of history.

R4S:

Do you have other examples?

TR:

Too many to list! Voting rights are at risk with more and more states involved in gerrymandering. Passing all these local ordinances – for instance, not being able to have water in the voting line - it's just ridiculous. Moving voting boxes away from college campuses or out of majority-Black neighborhoods makes voting more difficult. We're right back where we were again.

R4S:

Black activists are currently leading the reparations movement across the country, and beyond compensation, they are demanding that the civil rights you’ve mentioned, among other rights, be restored. Why is it important that white people join this movement? And is there a historical precedent for that?

It’s important that Black people lead change, but white people must also work with us. After all, who knows best how the system works? The people who benefit from it.

TR:

Absolutely. It’s important that Black people lead change, but white people must also work with us. After all, who knows best how the system works? The people who benefit from it. But we have always had allyship with whites. For instance, an outcome of the Niagara Movement was the formation of the NAACP, which was a mixed-race group of people. When we had the Underground Railroad, many station masters were white. So yes, the movement needs everyone.

R4S:

One of the symptoms many white people are feeling is a sense of cognitive dissonance, a realization that the world we have created, the choices we have made, the beliefs we’ve been taught, the benefits of whiteness we’ve received – the system no longer makes sense. Our worldview is beginning to crack apart - the longer we continue down the path we’re on, the stronger the sense of cognitive dissonance becomes because we can’t ignore the damage that occurs in this system’s wake. How does this look on your side of the fence?

TR:

One of the best examples of cognitive dissonance that I could give is during apartheid in South Africa. Take, for instance, a white South African child who's sent off to boarding school at six years old. They're trying to figure out why this child is having nightmares and bedwetting. Well, she's being told in the classroom every day that the Black South Africans are monsters: they’re ugly, horrible.

When your own sense of reality conflicts with what you’re being taught, it inevitably messes you up. That’s exactly what’s happening here – our whole society is experiencing that sense of cognitive dissonance you’re talking about, and I believe it is destroying us.

I saw a picture in a classroom of a face with a broad nose, big lips, and dark skin. The kids were being taught that this face was ugly, bad, and negative. Another drawing featured thin lips and a thin nose: the white standard for beauty, intelligence, and so on.

Now, that six-year-old child grew up with a Black nanny. When she fell and scraped her knee, that nanny kissed her knee and put the band-aid on it. She held her and hugged her when she was sick with a cold. That nanny was up with her during the night, caring for her as a baby. The child came to love that nanny.

Now, her teacher tells her that the very person she held dear is a monster. When your own sense of reality conflicts with what you’re being taught, it inevitably messes you up. That’s exactly what’s happening here – our whole society is experiencing that sense of cognitive dissonance you’re talking about, and I believe it is destroying us.

No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.

Frederick Douglass

R4S:

Why do you feel education is an important component of the movement for reparations?

TR:

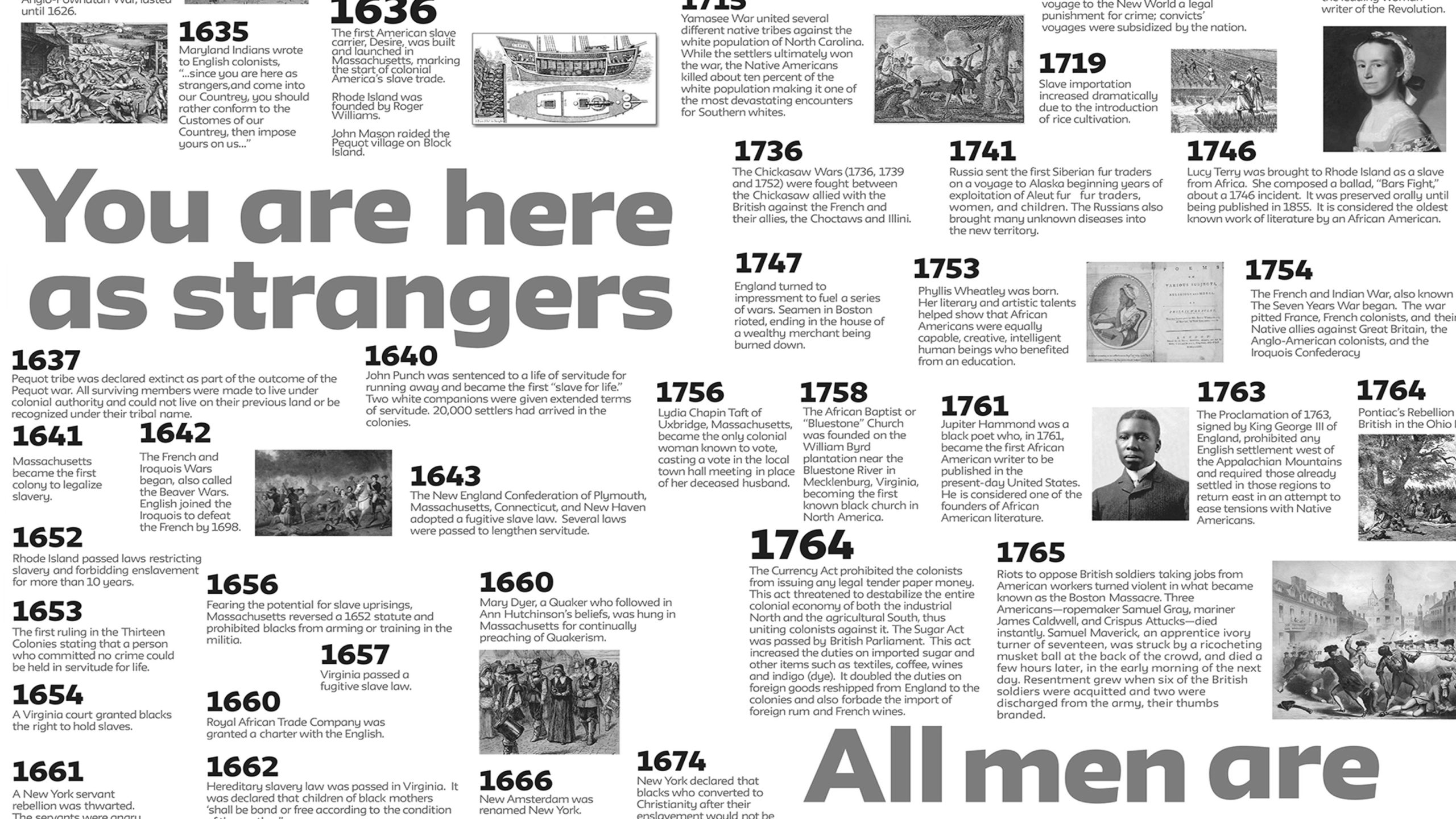

If you can read, write, and think you can do anything, you have power. To understand why reparations are necessary, you need to know your history. And that's why I like to start courses at the beginning, in Africa, because we've been lied to about this history for so long. I remember when people would say, “We're gonna study Africa and Egypt.” And I would say, “Well, when I went to bed last night, Egypt was still on the continent of Africa.” Why is it separated out? You have people believing that Egyptians were white, that’s why. They were not white.

When Black people study Black history, we develop pride in our heritage because we have done great things since the beginning of time. So, whether you're studying ancient Kemet or the Sahel Corridor, where we had some of the greatest systems of trade that ever existed, or West Africa - we have made outstanding contributions to this world. Everything from systems of law and finance, taxation, astronomy, math and science, even the cultivation of rice. The wealthiest man in history, Mansa Musa, was a 14th-century ruler of West Africa. Compare that to what we usually see – Black babies with flies in their eyes and distended bellies, poverty. It makes me furious that we’re depicted that way when we have such a rich history.

R4S:

Across the country, Black history programs are being dismantled, and courses canceled. In Florida, slavery is being recast as providing “employment training” to the enslaved. Could you talk a bit about why the argument that ‘enslaved people gained skills’ is fallacious?

TR:

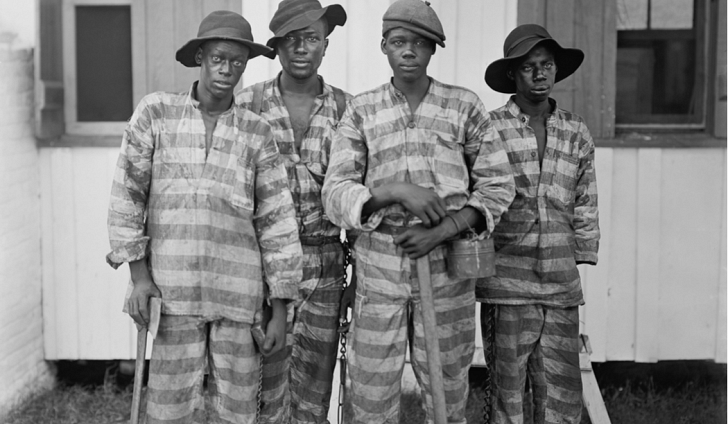

Black people were brought here intentionally for our skills. This was not a random act – it was a specific strategy. They knew what skills we had. Consider the Roanoke Colony – over 100 English settlers arrived in 1585 in an area that is now North Carolina. But they disappeared within 5 years. Why? Because they didn't have the skills to survive there. So, they brought us over because we know how to plant. We had previous interactions with Europeans, so we were resistant to their diseases. Enslaving Native Americans had already failed. One, because they could get away, they knew the land. Two, they were dying from disease because they had no immunity. And three, enslaving whites through indentured servitude did not work out well because they could run away and blend in with other groups. So, Africans rose to the top of the scale for that purpose. We were highly visible, and we came from agrarian cultures. We literally built this country, and that's what white people don't want to accept.

R4S:

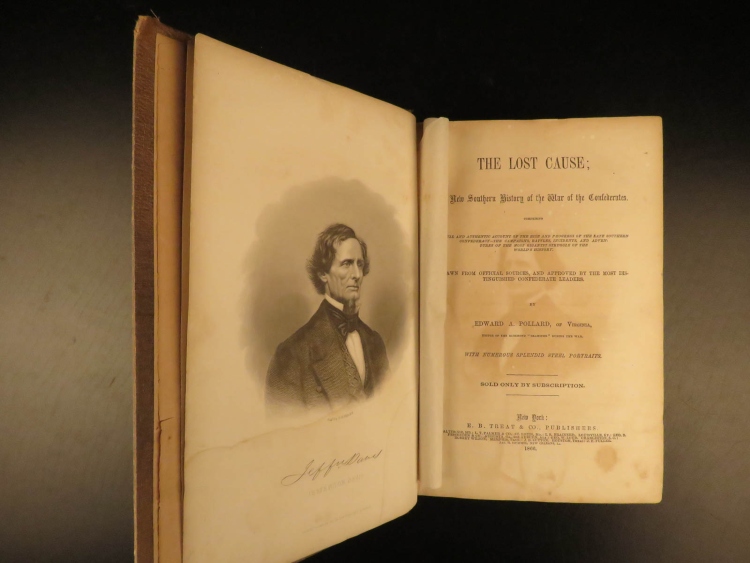

Groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy have made it their mission to ensure that the Lost Cause Mythology replaces a truthful account of both the Civil War and our history of slavery. Do efforts to restore this history serve as an act of repair?

Yes, truth-telling is a form of repair. These stories need to be told. Just because it's a traumatic part of our history doesn't mean that you cover it up. A balanced recounting is critical.

TR:

Yes, truth-telling is a form of repair. These stories need to be told. Just because it's a traumatic part of our history doesn't mean that you cover it up. A balanced recounting is critical. For instance, if I was a Southern planter's wife during the Civil War and the Union had overrun my plantation, I'm certainly going to have a different story and perspective than a Black Union soldier from the North. Both perspectives need to be expressed. But the bottom line is this: do not forget the context: in order for the planter’s wife and her husband to amass all that they owned, a group of human beings had to be subjugated, made subhuman. You've got to tell the whole story; then, every perspective can be heard. Without context, the lessons of the past are lost.

R4S:

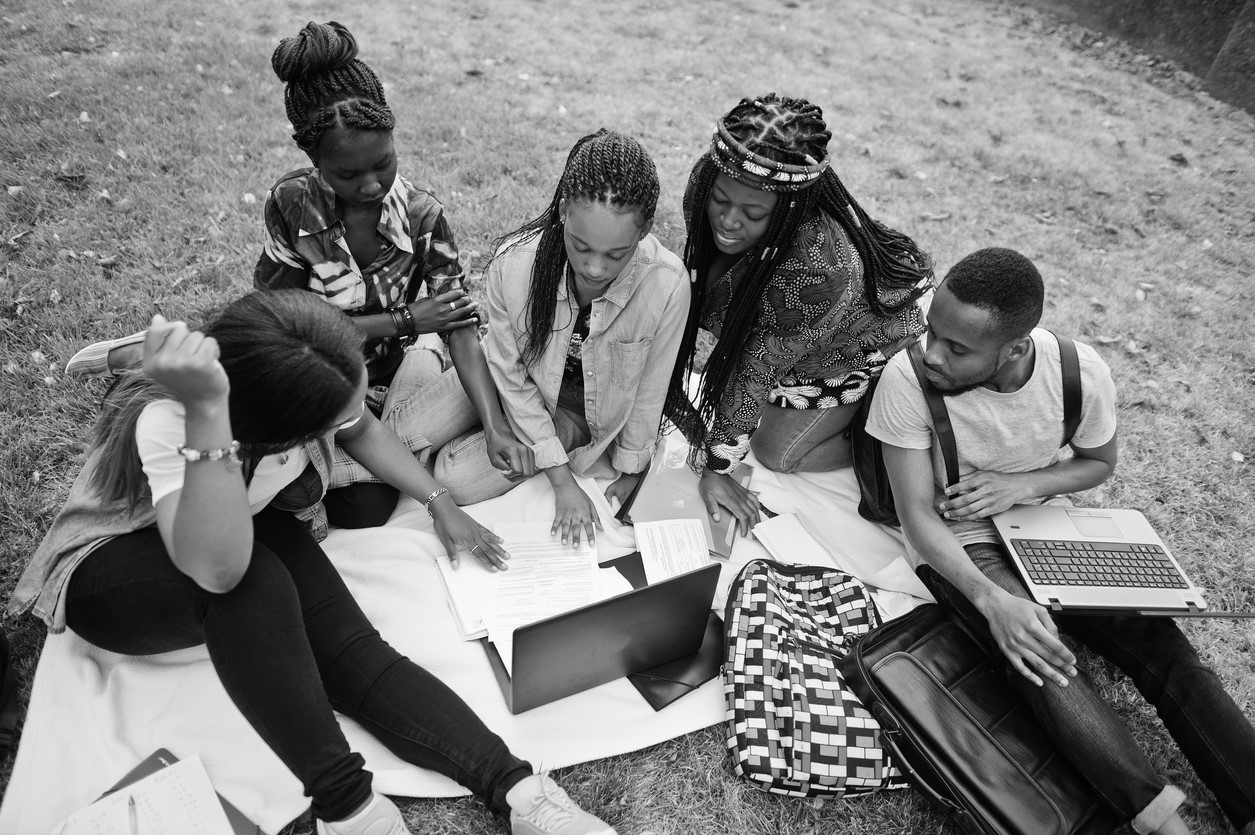

You co-led a 40-session reparations education series, Uncovering History: Walking the Path of Repair, over two years, which led participants through an accounting of US history that focuses on uncovering the sources of the racial wealth gap as the basis for the reparations movement. Why is it important that Black and white people study this history together and compare notes?

TR:

A lot of lying has been done in our classrooms over the years – putting people together who have had very different experiences gives them the opportunity to dissect this history together so we can move toward a more truthful accounting.

R4S:

What was your favorite part of that series?

TR:

When we covered the criminal injustice system. I had just covered the topic of convict leasing, including Sugarland, the Chattahoochee brick company, and Parchman Farm - those prison systems and the intense cruelty there. Students were meeting in their breakout groups and were charged with discussing parallels with modern-day policing.

How do you fix a system that works the way it was meant to work?”

We were dealing with the aftereffects of George Floyd and other police killings, and they were charged, as an exercise, with fixing the system. Of course, people had more questions than solutions. And my response to them was, “Did you look at how the system was formed and its intent in the first place? How do you fix a system that works the way it was meant to work?” And the epiphany, I mean, just looking at the faces as people got it. And then trying to grapple with how we make positive change. That was one of the best moments for me – when people see the throughlines of our history, from slavery through the present time, and suddenly see the whole picture.

R4S:

At the end of this series, we tested both Black and white members: Did they understand the history? Could they speak about the throughlines of history in terms of what we're experiencing today in the topics we covered? Could they describe how their families were impacted by this history, positively or negatively?

How do you think our cohort fared?

TR:

Not only did people gain general knowledge of the history, but they were introduced to areas that piqued their interest. It might've been environmental racism or criminal injustice; heir’s property and land theft were powerful topics. Once you find your area, you can really begin working toward repair. Watching that process and seeing people get excited about this work was wonderful. We had one student in particular who is now attending reparations strategy sessions all over the country and many of the others are engaged in their local areas.

R4S:

Any last thoughts you’d like to leave us with?

TR:

I want to underscore – learning this history is vitally important, particularly looking at how oppressive structures and systems were put into place. If you don't understand this history, you can't begin to repair it. That's the key thing.

When a country’s values speak of equality, but the systems and structures it puts in place intentionally hold back a segment of its society, those values become lies. Now, we could live up to those values if we had the will, as a country, to do so. The first step would require a process of truth-telling and repair.

I like to look at the idea of legacy. America was envisioned to be the greatest country in the world. And we are a country like no other, where every kind of people you can imagine have been brought together. The possibilities are endless. But the reality is deeply flawed - when a country’s values speak of equality, but the systems and structures it puts in place intentionally hold back a segment of its society, those values become lies. Now, we could live up to those values if we had the will, as a country, to do so. The first step would require a process of truth-telling and repair.