Modern Vectors of Economic Oppression

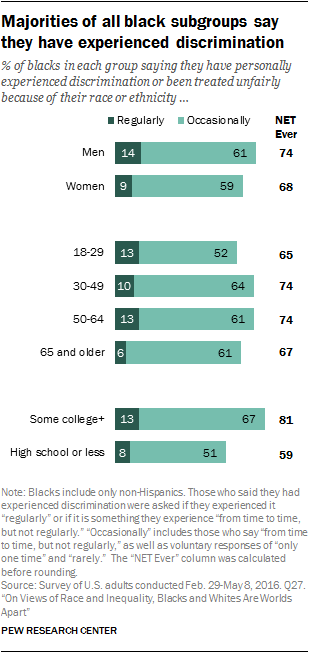

White Economic Advantage + Black Economic Suppression = Modern Vectors of Economic Racism

To facilitate change and unwind harm, we must first understand the damage we have done.

Efforts toward repair will only be successful when white families have studied the history of enslavement and its aftereffects, understood our own family's role in upholding white supremacy, and investigated how vestiges of the enslavement era live on in our communities, contributing to the racial wealth gap.

Systemic racism infects every corner of our daily life. Yet, to the extent we live in a white bubble, we may not even notice. However, there are compelling reasons why overcoming racism in our economy is vitally important. According to the W.K. Kellogg Foundation's 2018 report, "The Business Case for Racial Equity, a Strategy for Growth," racism is negatively affecting the US G.D.P.

The United States economy could be $8 trillion larger by 2050 if the country eliminated racial disparities in health, education, incarceration and employment, according to "The Business Case for Racial Equity: A Strategy for Growth." The gains would be equivalent to a continuous boost in GDP growth of 0.5 percent per year, increasing the competitiveness of the country for decades to come.

Consider each area documented in the chart below. Read each section, then research conditions in your community.

Coming soon:

Throughlines, a 16-part video series on the racial wealth gap.

Watch the Demo:

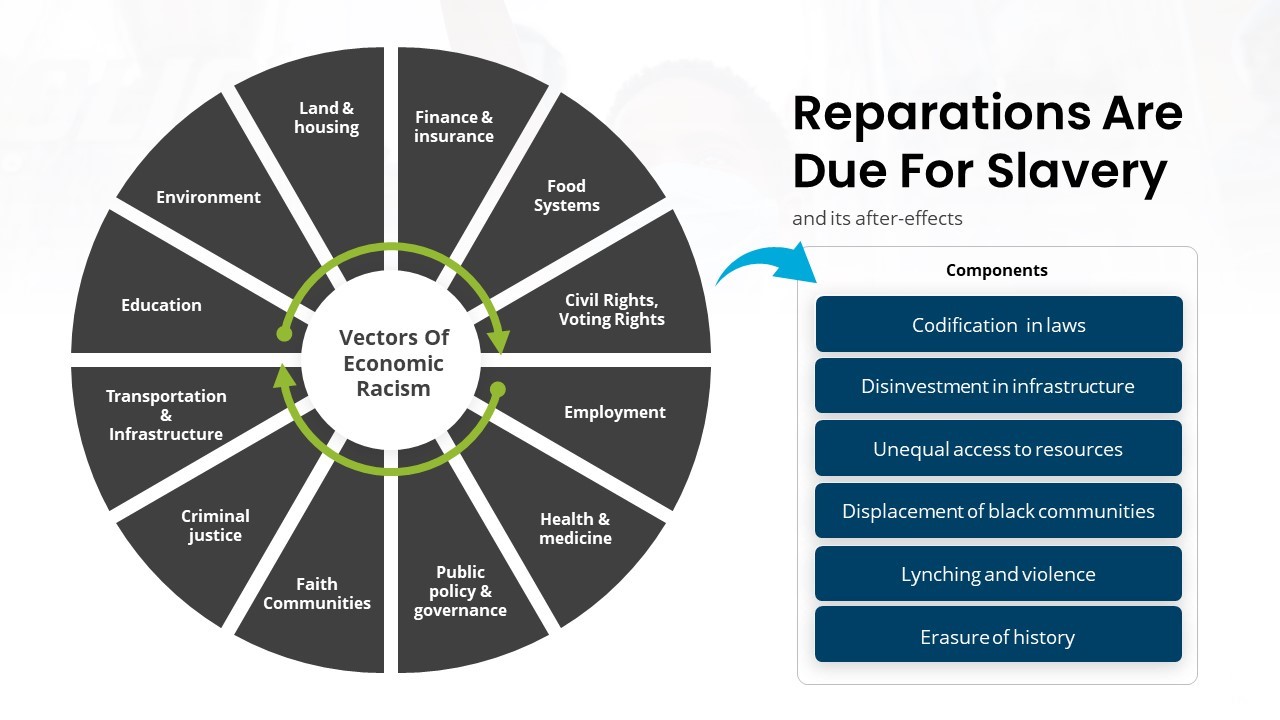

"For the (racial wealth) gap to be closed, America must undergo a vast social transformation produced by the adoption of bold national policies, policies that will forge a way forward by addressing, finally, the long-standing consequences of slavery, the Jim Crow years that followed, and ongoing racism and discrimination that exist in our society today."

W. Darity, D. Hamilton, M. Paul, A Aja, A. Price, A. Moore, and C. Chiopris

Learn about each modern vector of economic racism below:

Reckoning with an Unjust Past: a Spoken Word Series by Veronica Wylie

Summary

One Million Black Families in the South Have Lost Their Farms - Equal Justice Initiative

"Black landowners in the South have lost 12 million acres of farmland over the past century—mostly from the 1950s onward. The Atlantic reports that a million Black families have been ripped from their farms in a “war waged by deed of title” and propelled by white racism and local white power.

The dispossession of 98% of Black agricultural landowners in America is part of our history of racial injustice that is hugely important but mostly overlooked.

First, rich farmland in the South, especially along the Mississippi River, was taken from Native Americans by force. It was cleared, irrigated, planted, and reaped by enslaved Africans, who came to own part of it after emancipation.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there were 25,000 Black farm operators in 1910, an increase of almost 20% from 1900. The Atlantic‘s reporting focuses on Black farmland in Mississippi, which totaled 2.2 million acres in 1910—about 14% of all Black-owned agricultural land in the country, and the most of any state.

Later, through a variety of means—sometimes legal, often coercive, in many cases legal and coercive, occasionally violent—farmland owned by Black people came into the hands of white people. It was aggregated into larger holdings, then aggregated again, eventually attracting the interest of Wall Street.

Starting with New Deal agencies in 1937, federal agencies whose “white administrators often ignored or targeted poor Black people—denying them loans and giving sharecropping work to white people” became “the safety net, price-setter, chief investor, and sole regulator for most of the farm economy in places like the Delta.” As small farms failed, large plantations grew into huge industrial mega-farms with enormous power over agricultural policy.

Illegal pressures applied through USDA loan programs created massive transfers of wealth from Black to white farmers in the period just after the 1950s. Half a million Black-owned farms across the country failed between 1950 and 1975. Black farmers lost about six million acres from 1950 to 1969. Black-owned cotton farms in the South almost completely disappeared, and in Mississippi from 1950 to 1964, Black farmers lost almost 800,000 acres of land, which translates to a financial loss of more than $3.7 billion in today’s dollars, The Atlantic reports.

While most of the Black land loss appears on its face to have been through legal mechanisms—“the tax sale; the partition sale; and the foreclosure”—it mainly stemmed from illegal pressures, including discrimination in federal and state programs, swindles by lawyers and speculators, unlawful denials of private loans, and even outright acts of violence or intimidation.

Discriminatory loan servicing and loan denial by white-controlled, federally funded committees forced Black farmers into foreclosure, and their property was purchased by wealthy white landowners."

Quote

“If you are looking for stolen black land, just follow the lynching trail.” says Ray Winbush, director of Risk University’s Race Relations Institute.

Personal Narratives

"IN THE SPRING OF 2011, the brothers Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels were the talk of Carteret County, on the central coast of North Carolina. Some people said that the brothers were righteous; others thought that they had lost their minds. That March, Melvin and Licurtis stood in court and refused to leave the land that they had lived on all their lives, a portion of which had, without their knowledge or consent, been sold to developers years before. The brothers were among dozens of Reels family members who considered the land theirs, but Melvin and Licurtis had a particular stake in it. Melvin, who was 64, with loose black curls combed into a ponytail, ran a club there and lived in an apartment above it. He’d established a career shrimping in the river that bordered the land, and his sense of self was tied to the water. Licurtis, who was 53, had spent years building a house near the river’s edge, just steps from his mother’s.

Their great-grandfather had bought the land a hundred years earlier, when he was a generation removed from slavery. The property — 65 marshy acres that ran along Silver Dollar Road, from the woods to the river’s sandy shore — was racked by storms. Some called it the bottom, or the end of the world. Melvin and Licurtis’ grandfather Mitchell Reels was a deacon; he farmed watermelons, beets and peas, and raised chickens and hogs. Churches held tent revivals on the waterfront, and kids played in the river, a prime spot for catching red-tailed shrimp and crabs bigger than shoes. During the later years of racial-segregation laws, the land was home to the only beach in the county that welcomed black families. “It’s our own little black country club,” Melvin and Licurtis’ sister Mamie liked to say. In 1970, when Mitchell died, he had one final wish. “Whatever you do,” he told his family on the night that he passed away, “don’t let the white man have the land.”

Many assume that not having a will keeps land in the family. In reality, it jeopardizes ownership. David Dietrich, a former co-chair of the American Bar Association’s Property Preservation Task Force, has called heirs’ property “the worst problem you never heard of.” The U.S. Department of Agriculture has recognized it as “the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss.” Heirs’ property is estimated to make up more than a third of Southern black-owned land — 3.5 million acres, worth more than $28 billion. These landowners are vulnerable to laws and loopholes that allow speculators and developers to acquire their property. Black families watch as their land is auctioned on courthouse steps or forced into a sale against their will..."

******************************

“Land speculators ruthlessly exploited tax delinquency laws to defraud and dispossess poor, often elderly African Americans of their property holdings. In one instance, a White speculator befriended Evelina Jenkins, an African American woman who owned an entire island on the South Carolina coast, and convinced her to allow him to handle her financial affairs, including her property taxes. But instead of delivering Jenkins’s property tax payments to the county treasurer’s office, he purposely allowed her property to fall into tax delinquency, whereupon he successfully acquired the lien at the county’s tax auction. Following the close of the redemption period, he obtained the deed and had Jenkins evicted. He subsequently sold the land to a developer. Today, dozens of vacation homes, each worth upwards of $500,000 fill the island Jenkins formerly owned. Jenkins, meanwhile, was forced to move into a trailer home with one of her daughters, where she died penniless at the age of ninety in 1997.” -Andrew W. Kahrl[4]

Methods of Discrimination

- Heir's property legal complications and developer exploitation

- Many African Americans have died without wills leaving their property equally to all heirs

- Any heir may force a sale of the rest of the parcels

- Opportunists may purchase property from a single heir, then force the sale of the rest of the parcels

- Heir's property owners may not apply for many USDA farming programs; many Black farmers are denied benefits

- Racial discrimination in administration of the Homestead Acts

- KKK and violence leading to loss of land

- Unscrupulous sharecropping contracts

- lack of access to outdoor activities / lack of green and open spaces in majority Black communities

****************************************

“There is this idea that most blacks were lynched because they did something untoward to a young woman. That’s not true. Most black men were lynched between 1890 and 1920 because whites wanted their land.”

- Ray Winbush, the director of the Institute for Urban Research, at Morgan State University

Timelines of Disparity

Timeline: Black Land Loss and Discrimination in Agriculture (arcgis.com)

1863

The Emancipation Proclamation passes, freeing enslaved persons without providing the right to own land.

1865

One of the most promising events of the Reconstruction era occurred in Savannah, Georgia, where William Tecumseh Sherman issued Field Order #15, which allowed freed people to cultivate parts of the Georgia and South Carolina coasts and the Sea Islands. Through this decree Sherman sought to help former enslaved Africans become self-sufficient.

The Ku Klux Klan, a terrorist organization, originated in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1865, but quickly spread to other southern states. Designed to intimidate African-American southerners and their allies, and to re-establish white supremacy in the New South, the Klan unleashed a campaign of violence which suppressed African-American civil rights and prompted thousands of African-American southerners to exit their homeland.

Congress then passed legislation granting "not more than 40 acres of land" to "every male citizen, whether refugee or freedman," but the bill died when President Andrew Johnson vetoed it.

1877 - First Great Migration

Federal protection of African-Americans in the South ends. This paves the way for Jim Crow era, which starts over a decade later. Oppressive conditions spur The Great Migration, a near century-long migration north and west by 6 million African-Americans. This migration is a prime catalyst for the development of racially motivated zoning and housing policy by local, state, and federal governments that unfolds in stages over the next century

J. W. Carter, an African- American minister and farmer, formed the "Colored Farmers' Alliance," an organization designed to encourage cooperative buying among its members and to address the excesses and exploitation of businesses and banks.

Despite the efforts of the Colored Farmers' Alliance most African- American farmers remained uninformed about the use of modern agricultural methods.

1892

Booker T. Washington, seeking to improve the situation of African-American farmers, convened a conference at the Tuskegee Institute. Washington insisted that the more land African-Americans owned and cultivated the sooner they would get their rights.

Yet such activities were not able to reach the majority of African-American agrarians who remained virtual enslaved by the sharecropping system. Borne down by ever-increasing debts, trapped by a legal system which severely restricted their every movement, weakened by malnutrition and disease, and violently denied access to legal relief, African-American tenant farmers labored under a weight of oppression which offered virtually no escape.

The terror of lynchings accompanied the legalization of segregation as between 1890 and 1920 approximately 3,000 black men, women, and children lost their lives to lawless white mobs. These events, among others, so inflamed race relations in the South that 1 million African Americans abruptly fled southern communities for northern cities in search of their "Promised Land"

1933

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation instituted “redlining” policies that declared that mortgages in black neighborhoods were too risky—thus denying black Americans the opportunity to build wealth during the 1950s middle-class boom.

1933

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (initiated in 1933 to assist poor, rural Americans) and The Farm Security Administration, marginalized African-American farmers at the expense of the white-American tenant farmers due to policies that negated options of ownership for African-American farmers. During this time, African-American farmers also had substantially fewer sources of credit, more expensive credit when available, and an absence of legal redress in terms of contracts

1940

The Standard Rehabilitation Loan program was designed for high risk farmers regardless of color of skin, yet the ratios of utilization for white farmers versus black farmers were overwhelmingly high in favor of white farmers.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights criticized the USDA for using “the current condition of the Negro farmer” to limit access to resources necessary “to change his disadvantaged status.” USDA, the commission charged, “[divorced] the Negro from its regular concerns, designing for him limited objectives and constricted roles.”

The Southern Federation of Cooperatives is incorporated. It helped black farmers and their land loss to become a visible problem with both the black community and the country as a whole. SFC's mission remains that of improving conditions for farmers and their families via cooperatives and credit unions, safeguarding land ownership among black families, and advocating in terms of public policies that would be beneficial.

The United States Commission on Civil Rights found that USDA’s Farmers Home Administration —the nation’s leading public lending institution for rural communities at the time that was established in August 1946 to replace the Farm Security Administration—had been so unresponsive to the needs of black farmers that it “may have hindered the efforts of black small farmers to remain a viable force in agriculture.”

The Minority Farmers Rights Act, authorized to distribute $10 million in technical assistance to minority farmers, actually delivered only $2/3 million and in 2002 it was in danger of being defunded.

1994

Under the Freedom of Information Act, the Land Loss Prevention Project and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives investigated discriminatory practices by the USDA in the 1980s and 1990s. 1,000 African-American farmers filed a $3.5 billion class action suit against the USDA in 1996 alleging discriminatory actions such as denial of loans, disaster relief, etc. during those years. This led to the Pigford Class Action Suit, initiated by North Carolina native Tim Pigford and 400 other African American farmers in 1997.

1999

Judge Paul L. Friedman of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia approved a settlement agreement and consent decree in Pigford v. Glickman, a class action discrimination suit between the USDA and black farmers. The suit claimed that the agency had discriminated against black farmers on the basis of race and failed to investigate or properly respond to complaints from 1983 to 1997.

In the period between 2006 and 2016, the USDA foreclosed on black-owned farms at a higher rate than on any other racial group between. And, while black farmers made up less than 3% of USDA’s direct-loan recipients during that period, they made up more than 13% of farmers who were foreclosed on; the agency was more than 6 times as likely to foreclose on a black farmer as it was on a white one.

A lawsuit was filed in August by the National Black Farmers Association, seeking to stop agribusiness giant Bayer from selling Roundup, its popular herbicide that has been linked to cancer in recent years. The lawsuit, filed in St. Louis, alleges that Black farmers are forced by the agricultural system to spray Roundup and therefore are at risk of developing cancer. The lawsuit argues that Monsanto, which was bought by Bayer in 2018, knowingly failed and continues to fail to adequately warn farmers about the dangers of glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup.

Metrics

The number of U.S. black farmers declined by 98 percent between 1920 and 1997[1].

“According to the Census of Agriculture, the racial disparity in farm acreage increased in Mississippi from 1950 to 1964, when Black farmers lost almost 800,000 acres of land. The Atlantic by a research team that included Dania Francis, at the University of Massachusetts, and Darrick Hamilton, at Ohio State, translates this land loss into a financial loss—including both property and income—of $3.7 billion to $6.6 billion in today’s dollars[5].”

**********************

"Black land at Risk: The U.S. Department of Agriculture has recognized “heirs’ property,” or property that is inherited without use of a will as “the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss.” Heirs’ property is estimated to make up more than a third of Southern black-owned land — 3.5 million acres, worth more than $28 billion. These landowners are vulnerable to laws and loopholes that allow speculators and developers to acquire their property. Black families watch as their land is auctioned on courthouse steps or forced into a sale against their will."[8].

*********************

"Land ownership has always been a means to generate, accumulate and store wealth.

While many white settler families acquired property through government land grants and patents during the colonial era, and later through the Homestead Acts, Black families were largely precluded from accumulating real estate and amassing wealth – whether by legislative policy or through tactics of exploitation, intimidation, and fraud.

Why? Black landowners were considered more likely to vote, participate in public affairs and thus gain political power."[3]

Articles

[2] Historian Plumbs Tax Records for Patterns of Racial Discrimination | UVA Today (virginia.edu)

[4] "Unconscionable: Tax Delinquency Sales as a Form of Dignity Taking" by Andrew W. Kahrl (iit.edu)

[5] The Mississippi Delta’s History of Black Land Theft - The Atlantic

[6]Land and the roots of African-American poverty

[7] What Reparations Could Mean for Black Farmers | Civil Eats

Brea Baker: Making a Home on Black-Owned Land (elle.com)

Black farmers continue to battle systemic discrimination | Southern Poverty Law Center

Black Farmers Fear Foreclosure as Debt Relief Remains Frozen - The New York Times

Torn from the Land | The Authentic Voice

Who Owns Almost All America's Land? - Inequality.org

How USDA distorted data to conceal decades of discrimination against black farmers |

The Truth Behind '40 Acres and a Mule' | African American History Blog

Special Field Orders No. 15 - Wikipedia

How Did African-American Farmers Lose 90 percent of Their Land? - Modern Farmer

Black Lands Matter: The Movement to Transform Heirs’ Property Laws | The Nation

Farm Groups See Racism in Agriculture and Promise to Seek Change | Bloomberg Government

Adverse Racial and Community Impacts of Heirs’ Property Title Problems - Non Profit News

Jillian Hishaw Wants to Help Black Farmers Stay on Their Land | Civil Eats

The Homestead Act and the exodusters (article)

The Mississippi Delta’s History of Black Land Theft

The Promised Land: Plantation turned beloved black community

Opinion | Stalled US Debt Relief Is the Latest Setback to Black Farmers | Elisha Brown

Books

Systematic Land Theft by Jillian Hishaw | Goodreads

Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction by Nell Irvin Painter

Heirs' Property in the African American Community by Anderson Jones

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land by Leah Penniman

Podcasts

1619 Episode 5: The Land of Our Fathers, Part 1 - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

1619 Episode 5: The Land of Our Fathers, Part 2 - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Losing ground | Reveal (revealnews.org)

Sustained - Land Theft in the American Heartland

Fighting for the Promised Land: A Story of Farming and Racism | Southern Foodways Alliance

How southern black farmers were forced from their land, and their heritage

How Black Farmers Lost 14 Million Acres of Farmland — And How They're Taking It Back

Film/Video

How Property Law Is Used to Appropriate Black Land

Housing Discrimination: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver

The Biggest Problem You've Never Heard Of - Examining Heirs Property and Black Property Loss

Voices of the Civil War Episode 36: "Special Field Orders, No. 15"

How Black Americans Were Robbed of Their Land

How black farmers were forced from their land

Disrupt and Dismantle | Season 1 | Episode 3 | The Battle for Black Land

Websites

Arphax - Family Maps and Texas Land Survey Maps - Genealogy History

More

See additional sections Housing and Banking/Credit for related information.

Questions for Research and Reflection:

Which myths based in white supremacy culture did you grow up with?

- My ancestors worked hard to buy our land; we received no handouts from the government

- If Black people lost their land, it must be because they didn't work hard enough to keep it.

Ask older relatives or research on your own:

- Who were the first members of your family to own property? If you research your ancestors through census documents, did they rent or own? What year did they first acquire land?

- Did your ancestors receive any land grants? Is the land still in the family? What Native American tribes lived on the land before your ancestors were granted the land?

- Did your ancestors use wills and trusts to pass down inherited land to the next generation? What would have happened to that land if they had not had wills?

- In what ways do Heir's Property laws allow white developers and others to seize Black-owned land?

- How might the 1829 law forbidding enslaved people to learn to read or write impact future land acquisition and ownership?

- What are the tactics white people have historically used to drive Black people from their land? Create a list. Might your ancestors have acquired property by seizing Native American or Black owned lands? Why or why not?

- If Special Field Order 15 had not been rescinded, what would the median net worth of the descendants of Black families look like now?

Reckoning with an Unjust Past: a Spoken Word Series by Veronica Wylie

Check out the new format!

Summary

A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF HOUSING POLICY AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION (R.B. Drew)

Pre-20th Century Land and Housing Policies

Land ownership has always been restricted in the United States, even before it was an independent nation. Early European colonists claimed land from Native tribes and forced Native populations to live in designated districts separate from colonial settlements. As these settlements grew, colonial governments appropriated more territory from Native populations and limited their rights to own and sell property. In 1763 the British government offered some protection to Native lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, though following the American Revolution the new U.S. government invalidated the prior agreement and seized lands from Native tribes that had fought against the colonists.

Through the first half of the 19th century, as the United States continued its westward expansion and appropriation of even more Native lands, additional restrictions were placed on who could own property. Discrimination by race, as well as by religion and country of origin, was rampant, permitted by policies that either actively encouraged or did little to prevent it. In some states, free Black men were forbidden from purchasing land, and courts routinely invalidated gifts and other transfers of property to Black people. Even outside of slave-holding jurisdictions, opportunities for land ownership were often limited, either by direct law or the failure to regulate discriminatory practices against people of color.

Policies in the post-Civil War period continued to limit BIPOC property ownership. Prohibitions on Black land acquisitions increased following Emancipation in former slave-holding states, while exploitive practices like sharecropping entrenched existing racial power inequities. Elsewhere, socially, economically, and legally enforced residential segregation further prevented BIPOC from accessing housing and wealth-building opportunities. For example, Asian laborers brought to the U.S. in the late 19th century were often forced to live in ethnic enclaves and could not acquire property outside these designated districts, some of which evolved into the iconic Chinatown neighborhoods popular with tourists today.

A Very Brief History of Housing Policy and Racial Discrimination | Enterprise Community Partners

Personal Narratives

In 1954, Andrew Wade – an African American electrical contractor and Korean War veteran – wanted to purchase a house. A friend…suggested he look at a middle-class white neighborhood. The Wades found a property in Shively, an all-white suburb.

When the Wades and their child were moving in, a crowd gathered in front and a cross was burned on an empty lot next door. On the first evening…a rock crashed through the front window with a message tied to it: “Nigger Get Out,” and later that night ten rifle shots were fired through the glass of the kitchen door.

Under the watch of a police guard, demonstrations continued for a month until the house was dynamited.

"Remembering the Wades, the Bradens and the Struggle for Racial Integration in Louisville," (R. Howlett)

**********************

“In predominantly African American neighborhoods, where prospective homeowners struggled to obtain financing, Blair sold homes he had acquired via tax deeds on contract. This, in turn, allowed Blair to defraud another class of victims, extracting a substantial down payment from a buyer and then moving to have them evicted, and pocketing the contract buyer’s investment. This is what happened to Rufus Thomas, who purchased a house from Blair on contract in 1965. Shortly thereafter, Thomas received several citations for building code violations, which, as stipulated in the contract, he was required to correct. Contract sellers often sold homes that were in violation of numerous building codes, which the buyer was legally obligated to repair. This, as the historian Beryl Satter notes, often led contract buyers to miss payments and allowed sellers to repossess their homes) An unskilled laborer, Thomas drained his savings in an attempt to complete the repairs. When he failed to do so, he was hauled back into court and fined $2000. Prior to the hearing, Blair— acting as Thomas’s counsel—duped him into signing an affidavit stating that he was the sole owner of the property, which absolved Blair’s corporation of any liability. Unable to pay the fine, Thomas was sentenced to six months in jail.110 Upon sentencing, Blair served Thomas with a notice of forfeiture on his contract and moved to repossess the home.111 “In my dream, I’m caught in quicksand,” Thomas told a reporter. “I have my hands raised for help, but no help ever comes.”

"Unconscionable: Tax Delinquency Sales as a Form of Dignity-Taking" (A.W. Kahrl)

Methods of Discrimination

Deed Covenants

During the twentieth century, racially-restrictive deeds were a ubiquitous part of real estate transactions. Covenants were embedded in property deeds all over the country to keep people who were not white from buying or even occupying land; their popularity has been well documented in St. Louis; Seattle; Chicago; Hartford, Connecticut; Kansas City and Washington D.C. [5]

HOA Bylaws

After Shelley v. Kraemer, neighborhoods around the country, including in California, continued to bar African Americans and other racial minorities from purchasing property in their neighborhoods by creating community associations in which potential buyers would have to become members before purchasing property in the area. The white homeowners’ associations were often created by real estate developers.149 Because the bylaws of these associations restricted membership to whites only, they functioned to prevent African Americans from buying in those neighborhoods.[5]

Developer Loan Covenants

The government had an explicit policy of not insuring suburban mortgages for African Americans. In suburban Nassau County, just east of Queens, for example, Levittown was built in 1947: 17,500 mass-produced two-bedroom houses, requiring nothing down and monthly payments of about only $60.[3] (This was less than the approximately $75 unsubsidized charge in Woodside Houses for apartments of comparable size.[4]) At the FHA's insistence, developer William Levitt did not sell homes to blacks, and each deed included a prohibition of such resales in the future.[5][10]

Redlining

In the 1960s, sociologist John McKnight coined the term "redlining" to describe the discriminatory practice of fencing off areas where banks would avoid investments based on community demographics. During the heyday of redlining, the areas most frequently discriminated against were black inner-city neighborhoods. [11]

Physical intimidation – lynching, arson, complicity of law enforcement

History professor Andrew Kahrl in his book This Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth found that local officials in the Coastal South routinely assessed Black property owners at highly inflated rates in an effort to tax them off the land[2].

At the federal level, comparatively higher property taxes, along with federally standardized appraisal guidelines placed a lower value on property in Black or integrated neighborhoods, depressed the market value of Black-owned homes and severely limited the ability of African American families to build wealth through homeownership[3], [6].

Property Taxes/ Selective Reassessment

When Black people fought back, sudden and capricious hikes in property taxes via selective reassessment served as an effective, and ostensibly legal, form of intimidation [3]

Tax Liens

Tax liens were used to buy defaulted black properties for pennies on the dollar.

Blockbusting

Blockbusting is a business process of U.S. real estate agents and building developers to convince white property owners to sell their house at low prices, which they do by promoting fear in those house owners that racial minorities will soon be moving into the neighborhood. The agents then sell those same houses at much higher prices to black families desperate to escape the overcrowded ghettos. Blockbusting became possible after the legislative and judicial dismantling of legally protected racially segregated real estate practices after World War II. By the 1980s it largely disappeared as a business practice, after changes in law and the real estate market.[4}

Deed Theft

Through fraudulent means, BIPOC land and home ownership has been eroded by the theft of property deeds.

Criminalizing Deed Theft in Communities of Color - Word In Black

Timelines of Disparity

Full timeline of racial disparities in housing

1934

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) is created to boost home ownership during The Great Depression. The FHA insures home mortgages, but only for houses in white neighborhoods. This leads to the industry standard practice of redlining, which systematically withholds credit from homebuyers in black neighborhoods.

1938

Congress creates the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) to boost homeownership levels by making low-cost loans widely available. Only two percent of the $120 billion in new housing subsidized by the federal government between 1934 and 1962 goes to nonwhites.

1945

Though the GI Bill guaranteed low-interest mortgages and other loans, they were not administered by the VA itself. Thus, the VA could cosign, but not actually guarantee the loans. This gave white-run financial institutions free reign to refuse mortgages and loans to Black military members.

1968

Senators Walter Mondale (MN) and Edward Brooke (MA), then the only African-American member of the Senate, submit the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (S. 1358) for inclusion as an amendment within the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (H.R. 2516) a larger civil rights bill to protect civil rights workers.

2007

The subprime crisis reaches a peak. An epidemic of irresponsible mortgage lending driven by the high demand for mortgage-backed securities by institutional investors leads to a severe nationwide recession and nearly 10 million Americans losing their homes. Latinos and blacks experience nearly three times more foreclosure than whites, and decades of progress in their rate of homeownership is wiped out.

Metrics

- Breaking Down the Black-White Homeownership Gap | Urban Institute

- Income differences: 31% of the gap

- Differences in marital status: 27% of the gap

- Credit score differences: 22% of the gap

- Differences in educational attainment do not contribute to the gap

- 17% of the gap remains unexplained

Articles

Homeownership Gap / Housing Policy

Breaking Down the Black-White Homeownership Gap | Urban Institute

A Very Brief History of Housing Policy and Racial Discrimination | Enterprise Community Partners

Public Housing: Government-Sponsored Segregation (R. Rothstein)

Deed / Neighborhood Covenants

Documenting Racially Restrictive Covenants in 20th Century Philadelphia on JSTOR

Racists Deeds and Covenants (N. Watt, J. Hannah)

HOA Bylaws

Developer Loan Covenants

Loan Fraud / Discrimination

Redlining

[11] Redlining was banned 50 years ago. It’s still hurting minorities today. - The Washington Post

New Evidence on Redlining by Federal Housing Programs in the 1930s | NBER

Redlining: Mapping Inequality in Dayton & Springfield - ThinkTV

Appraisal Fraud

Racial Disparities in Home Appreciation (M. Zonta)

Home Appraisals More Likely To Be Lower in Black, Latino Areas Than White Ones : NPR

Property Taxes/ Selective Reassessment

Detroit overtaxed homeowners $600M. They're still seeking compensation (freep.com)

The Assessment Gap: Racial Inequalities in Property Taxation - Equitable Growth

Black Homeowners Pay More Than 'Fair Share' in Property Taxes | The Pew Charitable Trusts

Study of property taxes nationwide finds racial inequalities

Race for profit: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor on housing discrimination in America - Vox

Tax Liens

Blockbusting

Blockbusting and racial turnover in midcentury DC on JSTOR

Deed Theft

Criminalizing Deed Theft in Communities of Color - Word In Black

Segregation

[10] Public Housing: Government-Sponsored Segregation - The American Prospect

Disinvestment

How the Real Estate Boom Left Black Neighborhoods Behind - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Historian Says Don't 'Sanitize' How Our Government Created Ghettos : NPR

Violence

GI Bill

How the GI Bill's Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans

Books

1.Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor)

2.The Color of Law (Richard Rothstein) [9]

3.Segregation by Design (Jessica Trounstine)

4.How the GI Bill's Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans

Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City by Antero Pietila

Podcasts

VIDEO: Housing Segregation In Everything : Code Switch : NPR

Stuff You Should Know: How Housing Discrimination Works

Racial covenants, still on the books in virtually every state, are hard to erase : NPR

Websites

Film/Video

Race for Profit (Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor)

The Color of Law (Richard Rothstein)

How Redlining Shaped Black America As We Know It | Unpack That

Redlining and Racial Covenants: Jim Crow of the North

GOOD WHITE PEOPLE: A Short Film About Gentrification

Questions for Research and Reflection:

Which myths based in white supremacy culture did you grow up with?

- "If you just work hard enough, anyone can buy a house."

- "Segregation just happened; it reflects people’s natural choices to be apart."

- "Housing laws are applied fairly to everyone; racism can’t be a factor."

- "Redlining happened in the past; there are no effects of redlining remaining today"

- "Black people just don’t want to live here, that’s all."

- "Why do Black families default on their home loans? They’re just bad with money, I guess."

How would you respond to these statements today, after reviewing this learning module?

Ask older relatives or research on your own:

- When did your family first acquire a home?

- How was it acquired? Where?

- How easy was it to get a loan?

- Did your family receive GI Bill veteran's benefits to buy a home?

- How many Black families lived in your neighborhood growing up?

- Research redlining practices in your hometown – how does your neighborhood rate?

- Was your family's home in a blue or green-lined area?

- How does housing figure into your family’s net worth?

- Have ancestral homes been passed down through generations? What is the value of wealth that has been passed down?

- What zoning codes or neighborhood covenants in your neighborhood affect whether people of color live there?

- Are there any Black families living on your block? How well do you know them?

Reckoning with an Unjust Past: a Spoken Word Series by Veronica Wylie

Summary

While education is seen as key to social mobility, black people have faced significant barriers to academic success. While the Boston Latin School, the first school for whites, was established in 1635, public schools for Black children were not established until the mid-1800s. Colonists and slaveholders relied on ignorance and lack of literacy among enslaved people as a means of establishing and maintaining economic, political and social advantage. Basic information, literacy training, skill-sharing, and later pre-school education was accomplished through membership in Black churches and faith organizations.

Unequal Opportunity: Race and Education

"W.E.B. DuBois was right about the problem of the 21st century. The color line divides us still. In recent years, the most visible evidence of this in the public policy arena has been the persistent attack on affirmative action in higher education and employment. From the perspective of many Americans who believe that the vestiges of discrimination have disappeared, affirmative action now provides an unfair advantage to minorities. From the perspective of others who daily experience the consequences of ongoing discrimination, affirmative action is needed to protect opportunities likely to evaporate if an affirmative obligation to act fairly does not exist. And for Americans of all backgrounds, the allocation of opportunity in a society that is becoming ever more dependent on knowledge and education is a source of great anxiety and concern.

At the center of these debates are interpretations of the gaps in educational achievement between white and non-Asian minority students as measured by standardized test scores. The presumption that guides much of the conversation is that equal opportunity now exists; therefore, continued low levels of achievement on the part of minority students must be a function of genes, culture, or a lack of effort and will (see, for example, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve and Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom’s America in Black and White).

The assumptions that undergird this debate miss an important reality: educational outcomes for minority children are much more a function of their unequal access to key educational resources, including skilled teachers and quality curriculum, than they are a function of race. In fact, the U.S. educational system is one of the most unequal in the industrialized world, and students routinely receive dramatically different learning opportunities based on their social status. In contrast to European and Asian nations that fund schools centrally and equally, the wealthiest 10 percent of U.S. school districts spend nearly 10 times more than the poorest 10 percent, and spending ratios of 3 to 1 are common within states. Despite stark differences in funding, teacher quality, curriculum, and class sizes, the prevailing view is that if students do not achieve, it is their own fault. If we are ever to get beyond the problem of the color line, we must confront and address these inequalities."[7]

*******************************************

“Children coming to school in poor health or with unstable housing are absent more frequently and cannot benefit from good instruction. Children who walk (or ride) to school through violent neighborhoods, or who return to these neighborhoods after school, are stressed and less able to focus on studies. Children with more frequently unemployed parents suffer from insecurity that affects learning[1].”

Personal Narratives

Beth Patin of New York

My name is Beth Patin. I went to a boarding school for high school in Alabama. To raise money for prom and different dances and things, our school would have slave auctions. Folks were allowed to raffle themselves off and stand up in front of everybody on an auction block. And if you bid the most money, then you got to keep that person for an entire day and make them do whatever you wanted. It really bothered me. I went to talk to the headmaster and they really weren't willing to change things, but they eventually changed the name to serf sales, I think by the time I had graduated.

I mean, it certainly makes you feel emotionally vulnerable and a little bit unsafe. When I think back to all the things my family had to endure to be able to just attend schools; my grandfather had to sue the board of education in order to desegregate schools in the state of Alabama. So access to education is something that I've learned to really appreciate and to have gotten all the way to the '90s, 30 years after my father desegregated schools, it makes you feel like you still don't belong there. We've had 30 years of participation, but it still is not a place that is safe for me.

How Racism Has Manifested Itself In Schools, As Recalled By Listeners : NPR

Methods of Discrimination

- Inequality of Property Taxation for Education

- School District Resistance to Desegregation

- Unequal Access to Preschool Programs

- Unequal learning facilities

- Lack of adequate educational materials, textbooks and supplies

- Lack of Black educators / dismissal of Black educators

- Underfunding of HBCUs / Withholding of Federal and State Funds

- Salary disparities among Black educators

- Systemic Bias by Teachers

- Lack of support for development of culturally appropriate curricula

- Racial disparities in discipline

- Racist acts by teachers, administrators, staff and students

- Gentrification of schools

- Legacy Admissions “An analysis commissioned by Students For Fair Admissions found legacy applicants were accepted at a rate of nearly 34 percent from 2009 to 2015. According to the report, that's more than five times higher than the rate for non-legacies over the same six-year period: just 5.9 percent[2].”

- Unequal Access to Scholarships

- Unequal Access to Student Loans

- Predatory lending in student loans

Timelines of Disparity

1865

Federal law prohibited enslaved Africans from learning to read or write [5] After emancipation, schools were established, but education was not equally funded.

1896

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation laws for public facilities as long as the segregated facilities were equal in quality,[2] a doctrine that came to be known as "separate but equal." The decision legitimated the many state laws re-establishing racial segregation that had been passed in the American South after the end of the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877).[6]

1945

The G.I. Bill created educational opportunities for veterans returning from WWII. Black veterans were excluded from many of the benefits white veterans enjoyed. (4)

1980

African American students are more isolated than they were 40 years ago[1]

Metrics

K-12 Disparity Facts and Statistics - UNCF

STATISTIC #1:

African American students are less likely than white students to have access to college-ready courses. In fact, in 2011-12, only 57 percent of black students have access to a full range of math and science courses necessary for college readiness, compared to with 81 percent of Asian American students and 71 percent of white students.

Learn more in these sources:

- College Preparation for African American Students: Gaps in the High School Educational Experience

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights Data Snapshot: College and Career Readiness

STATISTIC #2:

Even when black students do have access to honors or advanced placement courses, they are vastly underrepresented in these courses. Black and Latino students represent 38 percent of students in schools that offer AP courses, but only 29 percent of students enrolled in at least one AP course. Black and Latino students also have less access to gifted and talented education programs than white students.

Learn more:

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights Data Snapshot: College and Career Readiness

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2013-14 Civil Rights Data Collection “A First Look”

STATISTIC #3:

African American students are often located in schools with less qualified teachers, teachers with lower salaries and novice teachers.

Learn more:

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights Data Snapshot: Teacher Equity

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2013-14 Civil Rights Data Collection “A First Look”

STATISTIC #4:

Research has shown evidence of systematic bias in teacher expectations for African American students and non-black teachers were found to have lower expectations of black students than black teachers.

Learn more:

STATISTIC #5:

African American students are less likely to be college-ready. In fact, 61 percent of ACT-tested black students in the 2015 high school graduating class met none of the four ACT college readiness benchmarks, nearly twice the 31 percent rate for all students.

Learn more:

STATISTIC #6:

Black students spend less time in the classroom due to discipline, which further hinders their access to a quality education. Black students are nearly two times as likely to be suspended without educational services as white students. Black students are also 3.8 times as likely to receive one or more out-of-school suspensions as white students. In addition, black children represent 19 percent of the nation’s pre-school population, yet 47 percent of those receiving more than one out-of-school suspension. In comparison, white students represent 41 percent of pre-school enrollment but only 28 percent of those receiving more than one out-of-school suspension. Even more troubling, black students are 2.3 times as likely to receive a referral to law enforcement or be subject to a school-related arrest as white students.

Learn more:

STATISTIC #7:

Students of color are often concentrated in schools with fewer resources. Schools with 90 percent or more students of color spend $733 less per student per year than schools with 90 percent or more white students.

Learn more:

STATISTIC #8:

According to the Office for Civil Rights, 1.6 million students attend a school with a sworn law enforcement officers (SLEO), but not a school counselor. In fact, the national student-to-counselor ratio is 491-to-1, however the American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250-to-1.

Learn More:

- American School Counselor Association

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2013-14 Civil Rights Data Collection “A First Look”

STATISTIC #9:

In 2015, the average reading score for white students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) 4th and 8th grade exam was 26 points higher than black students. Similar gaps are apparent in math. The 12th grade assessment also show alarming disparities as well, with only seven percent of black students performing at or above proficient on the math exam in 2015, compared to 32 percent white students.

Learn More:

There is a clear lack of black representation in school personnel. According to a 2016 Department of Education report, in 2011-12, only 10 percent of public school principals were black, compared to 80 percent white. Eighty-two percent of public school educators are white, compared to 18 percent teachers of color. In addition, black male teachers only constitute two percent of the teaching workforce.

Learn More:

Articles

[2] Legacy Admissions Offer An Advantage - And Not Just At Schools Like Harvard (M. Larkin, M. Aina)

[4] How the GI Bill's Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans

[5] Anti-literacy laws in the United States - Wikipedia

[6] Plessy v. Ferguson - Wikipedia

[7] Unequal Opportunity: Race and Education

Most teachers are white. Most students aren't.

States underfunded Black land grants by $13B over 30 years (insidehighered.com)

K-12 Disparity Facts and Statistics | UNCF

Black students need changes to policies and structures beyond higher education (insidehighered.com)

Opinion | Virginia is proof that reparations for slavery can work - The Washington Post

How America's student-debt crisis impacts Black borrowers (businessinsider.com)

The Continued Student Loan Crisis for Black Borrowers - Center for American Progress

U.S. Education: Still Separate and Unequal | Data Mine | US News

Why America's Public Schools Are So Unequal - The Atlantic

California reparations task force links slavery to segregated schools (msnbc.com)

What the New Integrationists Fail to See | Black-Only Schools (city-journal.org)

The Segregation of Topeka's Public School System, 1879-1951 - Brown v. Board of Educatio

Jim Crow's Schools | American Federation of Teachers (aft.org)

65 Years After 'Brown v. Board,' Where Are All the Black Educators? (edweek.org)

How White Progressives Undermine School Integration - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

The Continued Student Loan Crisis for Black Borrowers - Center for American Progress

School History – Sumner Academy of Arts and Science (kckps.org)

Unequal Opportunity: Race and Education (brookings.edu)

Black women are more burdened by student loan debt. Senator Warren says cancellation could solve it

Books

Cutting School: Privatization, Segregation, and the End of Public Education by Noliwe Rooks

Affirmative Action for the Rich: Legacy Preferences in College Admissions by Richard D. Kahlenberg

The Lost Education of Horace Tate | The New Press

Podcasts

Introducing: Nice White Parents - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Speaking of Psychology: Understanding racial inequities in school discipline

Heinemann Podcast: Beyond Quick Fixes to Racial Injustice in Education

What Makes Us Human Podcast | The College of Arts & Sciences (cornell.edu)

Episode 120: How One District Learned to Talk About Race | Cult of Pedagogy

Film/Video

Legacy Admissions Favor The Rich And Wealthy

A look at the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education - Good Morning America

'Gaming The System'?: Here's How Legacy Plays A Major Role In College Admissions

How America's public schools keep kids in poverty | Kandice Sumner

How Black High School Students Are Hurt by Modern-Day Segregation | NowThis

Education gap: The root of inequality

The Pandemic of Black Student Loan Debt

(Re)Thinking Black Student Debt

Jane Elliott “Blue Eyes - Brown Eyes” Experiment Anti-Racism

Questions for Research and Reflection:

Which myths based in white supremacy culture did you grow up with?

- white children are naturally more intelligent than Black children

- Each student has an equal chance at success

- What’s good for my child is good for all children

- That neighborhood's school is no good because the residents don't care about education

- Taking my child out of public school does not affect students of color in our area.

Ask older relatives or research on your own:

- How did integration affect the quality of education Black students received? White students?

- How many family members attended private schools versus public? When did they start going to private school? Why?

- How did your parents’/guardians’ work schedules affect your ability to have assistance with your homework and school projects after school?

- Were you pushed/encouraged to go to community college instead of a four year university?

- Who carried/carries the financial burden of your higher education? Did multiple members of your family contribute to the cost?

- Did returning WWII veterans in your family take advantage of the GI Bill’s education benefits?

- What colleges did they attend?

- How did attending college funded by the GI Bill affect your family’s financial prospects?

- Where did you attend grade school? Were you bussed?

- Where did you attend college? How has it affected your net worth? How much college debt did you take on?

- Ask a Black colleague about their family’s experience with education: GI Bill, college attendance, student debt levels, bussing, affect on net worth.

- To what do you attribute the differences?

Reckoning with an Unjust Past: a Spoken Word Series by Veronica Wylie

Summary

Business Case for Racial Equity - July 2018

The United States economy could be $8 trillion larger by 2050 if the country eliminated racial disparities in health, education, incarceration and employment, according to "The Business Case for Racial Equity: A Strategy for Growth." The gains would be equivalent to a continuous boost in GDP growth of 0.5 percent per year, increasing the competitiveness of the country for decades to come. The national study released today by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) and Altarum concludes that while racial inequities needlessly stifle economic growth, there is a path forward.

The report projects a tremendous boost to the country's workforce and consumer spending when organizations take the necessary steps to advance racial equity. Led by Ani Turner, co-director of Sustainable Health Spending Strategies at Altarum, researchers analyzed data from public and private sources, including the U.S. Census, Johns Hopkins University, Georgetown University, Brandeis University and Harvard University.

************************

42% of U.S. employees have witnessed or experienced racism in the workplace.

Unfortunately, 93% of white workers do not believe racial or ethnic discrimination exists in their workplace.

Let’s talk about racism in the workplace. Do you feel uncomfortable already? That’s okay. Feelings of discomfort, denial and anger are normal reactions to something so reprehensible. But the fact that you clicked on this article says something: You want to learn. That’s a great first step.

Before we go over some tips for fighting racism in the workplace, let’s begin with some statistics and definitions so you can get a better idea of what it is and why it’s still wreaking havoc in our professional lives.

- 42% of employees in the U.S. have experienced or witnessed racism in the workplace. For Glassdoor's 2019 Diversity and Inclusion Study, The Harris Poll surveyed over 5,000 employees in the U.S., UK, France and Germany. Of the 1,113 U.S. workers surveyed, 42% agreed with the statement, "I have experienced or witnessed racism in the workplace”—the highest percentage of any of the countries included.

- 35% of Black workers believe racial or ethnic discrimination exists in their workplace, but only 7% of white workers believe the same. This is based on data from June 2020, when SHRM surveyed 1,257 U.S. workers for its Together Forward @Work report on racial inequity.

- In a 2020 experiment, Black women with natural hairstyles were rated as less professional than Black women with straightened hairstyles. They were also less likely to be recommended for an interview. The results of this study were published in the August 2020 edition of Social Psychological and Personality Science.

- “Whitened” resumes are more likely to get call-backs than resumes with ethnic-sounding names. This 2016 study was published in Administrative Science Quarterly and explored the many ways people of color might feel compelled to participate in "resume whitening," which includes tactics such as modifying their names, changing the way they presented their experience (such as deleting experiences that might clue others in to their minority status) and adding more "Americanized" interests.

In one of the experiments, researchers sent fictitious but realistic-sounding resumes to 1,600 real job postings; some of the resumes were whitened, and some had obvious signals of race. The results? Whitened resumes received more callbacks. For Black job applicants, 25% received callbacks for whitened resumes versus 10% for resumes with race details. For Asian job applicants, 21% received callbacks for whitened resumes versus 11.5% for resumes with race details. - On average, Black and Hispanic workers are paid less than white workers at almost every level of education. According to the Economic Policy Institute's State of Working America Wages 2019, Black workers with advanced degrees earned 82.4% of the wages that white workers with advanced degrees earned in 2019.

- Black professionals (31%) have less access to senior leaders at work than white professionals do (44%). This is based on data from Coqual’s 2019 Being Black in Corporate America report. The report highlighted disparities between perceptions as well. For example, while 65% of Black professionals say that Black employees must work harder than their colleagues to get ahead in their careers, only 16% of white professionals believe the same.

- In 2016, over 70% of Asian and Black workers in Britain said that they had experienced racial harassment at work in the previous five years. This is based on the answers of 5,191 people in Britain who participated in the 2016-2017 Racism at Work survey.

Personal Narratives

Racism and discrimination aren’t always easy to spot.

Sometimes it’s the small, subtle actions and assumptions that betray people’s racial biases – whether they’re at school, in the street or in the workplace.

An innovative VR project is trying to shed light on these lesser-known displays by letting viewers experience what it’s like to be turned down for a job – even through you’re the most qualified candidate.

The project’s creators hope that by slipping on a headset and into someone else’s shoes, those watching the video might be more aware of their own preconceptions in future situations.

********************

“Is This Because I’m Black?”: A Story of Racial Discrimination

By WENDY KELLY

"...Additionally, I remember applying for my first “real job” as a receptionist at a doctor’s office. I had arrived for the interview a little early, the waiting room was full of (mostly Black) candidates. I listened as the hiring manager, a doctor, called the candidates one-by-one for their interview: Keisha, LaQuitta, Otishia, Tishia. They’d go in and spend five minutes (maybe) with the doctor.

Now it was my turn. Wendy Kelly. I go in with a smile on my face, resume in hand, and a completed application. “Finally,” he says, “a person whose name I can pronounce. I thought you were white.”

I was so shocked at what I had just heard, I had no idea how to respond, so I sat and smiled. He never took my resume, only the application that he placed on his desk. He asked me two or three questions, and that was it. I left that interview confused, but I was not sure about what.

For some reason, I still wanted that job. Why?

I guess because I still wanted a “real job.” It wasn’t until I got home that I realized this man was a racist. I had no idea about the EEOC, so I called my state representative at the time, who was white and simply told me, “We will look into the matter, and someone will get back to you.” Twenty-five years later, I am still waiting..."

“Is This Because I’m Black?”: A Story of Racial Discrimination

Methods of Discrimination

Even having a “Black” sounding name can results in discrimination

- With all other aspects controlled, field research conducted in Chicago in 2003 revealed that white names yields as many more callbacks as an additional eight years of experience. The callback gap for the same resume with different names is 50%[3].

Having a Black sounding voice can result in discrimination

- Linguistics professor John Baugh found that people who sounded “white” in answering job advertisements were more likely to be told that the job was still available[4].

A study conducted in 2003 by Devah Pager of Northwestern University focuses on the relationship between incarceration and employment using matched pairs of people applying for the same jobs. She found that:

1.Employers are more likely to consider white candidates with criminal records than black candidates with no such history[e].

2.the effect of a criminal record is 40% greater for blacks than for whites. The ratio of callbacks for nonoffenders relative to ex-offenders for whites is 2:1, this same ratio for blacks is nearly 3:1.

The NBER paper, coauthored by Costas Cavounidis and Kevin Lang, of Boston University, attempts to demonstrate how discrimination factors into company decisions, and creates a feedback loop, resulting in racial gaps in the labor force[5].

1. Hiring discrimination can lead to more consistent or prolonged unemployment for Black people.

2. Gaps in employment enforce the prejudiced assumption that Black workers are less skilled

3. Employers are less likely to hire unskilled workers or treat them with skepticism if hired.

4. Black workers are more scrutinized (policed) than their white colleagues

5. Because black workers are more closely scrutinized, it increases the chances that errors will be caught

6. When black employees do err, they are more likely than their white colleagues to be let go.

7. This leads to more unemployment

US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was created as a part of the Civil Rights Act to investigate workers’ complaints of job discrimination.

1.“The EEOC is weak by design. When the EEOC was created under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it was initially given few tools to enforce the law. It could investigate complaints, try to mediate between companies and employees, and recommend cases to the US attorney general for litigation, but it couldn’t sue or issue cease-and-desist orders. If an employer didn’t want to follow the law, there was little the agency could do about it[6].”

2.“Just over a quarter of all EEOC complaints came from black employees alleging racial discrimination[6].”

3.“Each year, the EEOC and its state and local partner agencies close more than 100,000 cases — but workers receive some form of assistance, such as money or a change in work conditions, only 18 percent of the time[6].”

4.“Almost 40 percent of people who filed complaints with the EEOC and partner agencies from 2010 through 2017 reported retaliation[6].”

Metrics

“After controlling for age, gender, education, and region, black workers are paid 14.9% less than white workers[1]. Black women are paid 39% less or 61 cents for every dollar that a white man makes [2].”

Among college graduates the Black unemployment rate averaged 2.8 percent from November 2018 to October 2019, 40 percent higher than the 2 percent rate for white college graduates in the same period[2].

Articles

[1] Black-white wage gaps are worse today than in 2000 (E. Gould)

[2] African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs (C. Weller)

[5] Black Workers Really Do Need to Be Twice as Good (G. White)

[6] Workplace discrimination is illegal. But our data shows it's still a huge problem (J. M. Jameel)

What you probably didn’t know about racism in the workplace - Journal of Accountancy

“Is This Because I’m Black?”: A Story of Racial Discrimination

The Costs of Code-Switching in the Workplace

Code-Switching at Work Is Taking a Psychological Toll on Black Professionals

Study Highlights ‘The Costs of Code-Switching’ in the Workplace

Books

Race, Gender, And Discrimination At Work by Samuel Cohn

Podcasts

TruthWorks Network Radio - Working While BLACK l TruthWorks Network l Racial Bullying

How Does Race Affect Your Workplace? (hbr.org)

Podcast episode 14:Race, jobs, and the American postsecondary system (luminafoundation.org)

Protesting Her Own Employer - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Film/Video

Racial Discrimination in the Workplace

Black Americans in the Workplace | The Daily Social Distancing Show

How These Women Got Hair Discrimination Outlawed in NYC | NowThis

Discrimination in the workplace: Creating opportunities for black female professionals at work

Discrimination in America: African American Experiences

Race Bias in Hiring: When Both Applicant and Employer Lose (Podcast)

Questions for Research and Reflection:

What myths based in white supremacy culture did you grow up with?

- Everyone has an equal chance at a job

- If "they" just looked more professional, they would have a better chance getting that job

- Affirmative action has taken care of racial discrimination

- My work environment is all white because there are no qualified people of color in my industry

- Everyone is getting paid the same at work!

Ask older relatives and research on your own:

- Did your older relatives work with Black colleagues? How were they treated?

- Ask a Black colleague about their family’s experience in the workplace: how would they compare their experiences compared with white colleagues with similar educational backgrounds?

- To what do you attribute the differences?

Reckoning with an Unjust Past: a Spoken Word Series by Veronica Wylie

Summary

Personal Narratives

Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong

"Last month marked 100 years since Lacks’s birth. She died in 1951, aged 31, of an aggressive cervical cancer. Months earlier, doctors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, had taken samples of her cancerous cells while diagnosing and treating the disease. They gave some of that tissue to a researcher without Lacks’s knowledge or consent. In the laboratory, her cells turned out to have an extraordinary capacity to survive and reproduce; they were, in essence, immortal. The researcher shared them widely with other scientists, and they became a workhorse of biological research. Today, work done with HeLa cells underpins much of modern medicine; they have been involved in key discoveries in many fields, including cancer, immunology and infectious disease. One of their most recent applications has been in research for vaccines against COVID-19.

But the story of Henrietta Lacks also illustrates the racial inequities that are embedded in the US research and health-care systems. Lacks was a Black woman. The hospital where her cells were collected was one of only a few that provided medical care to Black people. None of the biotechnology or other companies that profited from her cells passed any money back to her family. And, for decades after her death, doctors and scientists repeatedly failed to ask her family for consent as they revealed Lacks’s name publicly, gave her medical records to the media, and even published her cells’ genome online..."[4]

[4] Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong

*********************

Racism and discrimination in health care: Providers and patients

"A patient of mine recently shared a story with me about her visit to an area emergency room a few years ago.* She had a painful medical condition. The emergency room staff not only did not treat her pain, but she recounted: “They treated me like I was trying to play them, like I was just trying to get pain meds out of them. They didn’t try to make any diagnosis or help me at all. They couldn’t get rid of me fast enough.”

There was nothing in her history to suggest that she was pain medication seeking. She is a middle-aged, churchgoing lady who has never had issues with substance abuse. Eventually, she received a diagnosis and appropriate care somewhere else. She is convinced that she was treated poorly by that emergency room because she is black.

And she was probably right. It is well-established that blacks and other minority groups in the U.S. experience more illness, worse outcomes, and premature death compared with whites.1,2 These health disparities were first “officially” noted back in the 1980s, and though a concerted effort by government agencies resulted in some improvement, the most recent report shows ongoing differences by race and ethnicity for all measures." [5]

Methods of Discrimination

Medical Experimentation, without anesthesia, during slavery-era

Rape, forced pregnancy

Medical Bias

Unequal Access to Care

Unequal Access to Medical Industry Jobs

Unequal Quality of Care

Unequal access to pain medications; assumptions that African Americans have a higher tolerance for pain.

Lack of medical protocols for African American populations

Unauthorized Use of Genetic Material

Forced Sterilization

Timelines of Disparity

150 Years Ago

Medical experiments were conducted on enslaved Africans, including gynecological procedures, and forced sterilization.

50 Years Ago

The Tuskeegee syphilis medical torture

In 2012 Researchers at University of California Santa Barbara ran an experiment to test the link between the anticipation of prejudice and increased psychological and cardiovascular stress.

“When Latina participants thought they were interacting with a racist white partner, they had higher blood pressure, a faster heart rate, and shorter pre-ejection periods. What this shows is an increased sympathetic response, or what is often called the "fight or flight response." Merely the anticipation of racism, and not necessarily the act, is enough to trigger a stress response. And this study only involved a three-minute speech[2].”

Metrics

Blacks people suffer a disproportionate burden of illness and chronic disease with worse outcomes than Whites. Blacks’ mortality rates are about 20% higher than those of Whites, resulting in a 4-year lower life expectancy.

- When Black people have access to medical institutions they receive poorer quality care than their white counterparts even when other factors like income are controlled.

Black children who lose a finger are half as likely as White children to have the finger reattached.

Blacks with peripheral arterial disease were 77% more likely than Whites to have the affected limb amputated; this disparity was greatest in the best-resourced medical facilities.

- Racial biases play a role in these health care disparities.

- Bias even exist in the technology developed by white people.

Hospital algorhythms routinely refer Black people to programs that provide less personalized care.

Articles

1.Cruel Medical Experiments on Enslaved people were widespread in the south

a.J. Marion Simms the “father” of modern gynecology experimented on enslaved women.

Medical Experiments on Black People extended into the modern era

a.Charity Patients Irradiated to Gauge Effect on Soldiers in through 1972

b.Tuskegee Experiments 1932-1972

New York Foundation Apologizes for Its Role in Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The plundering and capitalization of of Black genetic material

a. The Legacy of Henrietta Lacks

The 2020 race to capitalize on African Genomic material

Black Maternal Health Disparities

Black newborns 3 times more likely to die when looked after by White doctors - CNN

Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy-Related Deaths | CDC Online Newsroom | CDC

Why I Had To Fire My White Dermatologist? | by Rebecca Stevens A.

What Is ‘Medical Gaslighting’ and How Can You Elevate Health Care - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

More...

[1] Cruel Medical Experiments On Slaves Were Widespread In The American South (D. Vergano)

[2] How Racism Is Bad for Our Bodies (J. Silverstein)

[4] Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong

[5] Racism and discrimination in health care: Providers and patients

Opinion | No, Justice Alito, Reproductive Justice Is in the Constitution

Calling Out Racism in Nursing - Word In Black

Books

Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty by Dorothy Roberts

Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Health Care by Dayna Matthew

Black Queer Nurse by Britney Daniels

Podcasts

Black History Year - What You Need To Know About Medical Racism with Harriet Washington

Podcast: Racism as a public health issue – Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

History of American Slavery: Medical experimentation in slavery and the rise of scientific racism

Film/Video

It's Not Just About Tuskegee: The History of African Americans and Medicine

How Modern Medicine Was Born of Slavery

Harriet A. Washington: Discussing Medical Experimentation on Black Americans - 03/07/2017

Lack of Diversity in Health Care: A Health Disparity | Kiaana Howard, DPT | TEDxLenoxVillageWomen

Unpacking Bias in Seeking Mental Health Care for Women of Color | Chandra Carey | TEDxSMUWomen

The US medical system is still haunted by slavery

Questions for Research and Reflection:

Which myths based on white supremacy culture did you grow up with?

- Black people feel little pain.

- Black people are great at sports; they are physically different from white people.

- Sterilizing Black people is for their own good.

- Black people don't take care of themselves; that's why they are in poor health

- Doesn't everyone have good health insurance? What's so hard about getting a regular checkup?

- Diabetes? It's because "they" eat all that junk food. If "they" just ate a better diet and exercised, "they" would be in good health.

Self-reflection:

- Why has the COVID pandemic affected Black families at 3 times the rate of white families?

- Why might Black families not trust doctors?

- Are there any physicians in your family? Across multiple generations? What resources paid for this education?

- When you were growing up, did you have health insurance?

- Did you visit the doctor and dentist for regular checkups?

- How would you rate the care you received?

- What about now?

- Ask a Black colleague about the healthcare they received as a child, and the healthcare they receive currently.

- Compare quality and treatment

- Compare health outcomes in your families.

- What are your findings?

Reckoning with an Unjust Past: a Spoken Word Series by Veronica Wylie

Summary

Food Desert

“Grocery gaps, locales in which there are no grocery stores or other opportunities to purchase fresh, healthy food, which typically co-exist with “food swamps,” areas which have a high prevalence of unhealthy food options, such as fast food and convenience stores[1].”

During the 1940s, low-interest home loans offered to middle-class white families through the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration enabled them to move from cities to suburbs. Supermarkets followed white middle-class incomes to the suburbs in a process called white flight[1]. African American families were systematically denied access to these loans and when they could purchase homes they were relegated to purchasing homes in divested redlined areas. Because redlined areas were graded “high risk” by their association with African Americans, African American communities directly experienced retail divestment and became the “Food Deserts” that exist today.

Personal Narratives